Is it the bustling economy? Beautiful lakes? Great quality of life? All that, and more

Is it the bustling economy? Beautiful lakes? Great quality of life? All that, and more

By Susannah Felts

Photos by Steve Woit

Minneapolis may surprise you. Sixteen Fortune 500 companies call the area home. The economy is diverse and strong. Housing is affordable. The population skews younger than the U.S. average. Then there’s the beautiful lakes—more than a dozen inside city limits—and the top-rated parks system. Three major-league teams. It’s second only to New York City in the number of theater seats per resident. At No. 17, it’s the top-ranked Midwestern city in U.S. News & World Report’s latest edition of best places to live.

The evidence is unassailable: Minneapolis has a lot going for it.

Increasingly, Vanderbilt’s Owen School graduates are answering the city’s siren call, pursuing careers in the City of Lakes, each adding to the thriving alumni network in the area. While their professional roles vary widely, they uniformly voice a newfound appreciation for this Midwestern metropolis and a gratitude for the MBA program that prepared them. Meet five Vanderbilt MBA grads who call Minneapolis home.

The Consumer Goods Buyer

Armed with a mechanical engineering degree from Vanderbilt, Vanessa Rosario, BE’05, MBA’16, spent eight years at General Electric before coming back to campus for a business degree. The Cincinnati native thought, like many MBA grads before her, she’d settle in the South after business school—perhaps Nashville or Atlanta. But after completing a summer internship at Target halfway through graduate school, she couldn’t say no to Target’s offer of a role as senior buyer and a return to the Midwest. “It’s almost like running your own business within the business,” she says of her position.

Armed with a mechanical engineering degree from Vanderbilt, Vanessa Rosario, BE’05, MBA’16, spent eight years at General Electric before coming back to campus for a business degree. The Cincinnati native thought, like many MBA grads before her, she’d settle in the South after business school—perhaps Nashville or Atlanta. But after completing a summer internship at Target halfway through graduate school, she couldn’t say no to Target’s offer of a role as senior buyer and a return to the Midwest. “It’s almost like running your own business within the business,” she says of her position.

Originally planning to go into marketing, Rosario found her interest in brand management piqued once she started at Vanderbilt. Coaches at the Career Management Center urged her to explore the world of career conferences. It was at one such gathering where she first explored merchandising. “Going into business school, I hadn’t thought of that as an option I could have after getting my MBA,” she says. But the career path met a lot of her interests.

Rosario enjoys the breadth of involvement her role buying seasonal toys at Target requires. This spring, she planned the company’s product transition to fall, focused on what licensed properties might be hot six months into the future. Her work keeps her up on cultural trends and takes her to the annual New York Toy Fair, where innovators attempt to shake up the marketplace.

Back at the office, she keeps an eye on product margins and plans for how new products will appear in Target stores. “Strategy is a big piece of it,” she notes, “and I like that I’ve taken things I learned in all my courses at Owen and applied them to my career.”

Rosario lives in downtown Minneapolis, where she can walk to the Twins and Vikings stadiums and to work—even in the deep freeze of winter. “Downtown has miles of indoor skyways that connect the buildings,” she says. “I can pretty much walk everywhere. I don’t use my car much.”

Not that she hasn’t learned to embrace the (cold) outdoors. She and several friends tried ice fishing last winter, sleeping overnight in a cabin on a frozen lake. “It’s one of the things I just had to experience while I’m here,” she says.

The Cereal Marketer

As a senior associate marketing manager at General Mills, Devin Kunysz, MBA’15, manages a $400 million–dollar business: all the chocolate cereals produced by the company, including Cocoa Puffs, Reese’s Puffs and Cookie Crisp. The job involves a lot of marketing strategy, but Kunysz also works closely with the technological teams that develop products for the next generation. While he looks toward the future, there’s a long history of cereals in the marketplace to consider. Recently, Kunysz developed a campaign around the 60th birthday of Cocoa Puffs’ mascot, Sonny the Cuckoo Bird.

As a senior associate marketing manager at General Mills, Devin Kunysz, MBA’15, manages a $400 million–dollar business: all the chocolate cereals produced by the company, including Cocoa Puffs, Reese’s Puffs and Cookie Crisp. The job involves a lot of marketing strategy, but Kunysz also works closely with the technological teams that develop products for the next generation. While he looks toward the future, there’s a long history of cereals in the marketplace to consider. Recently, Kunysz developed a campaign around the 60th birthday of Cocoa Puffs’ mascot, Sonny the Cuckoo Bird.

“I wouldn’t be here if I didn’t go to Owen,” he says. “A Vanderbilt MBA is pretty much a chance to learn how to think about business in a new way, a chance to develop leadership skills and critical thinking skills, and Owen did a great job of that.” Kunysz found that projects he worked on at Vanderbilt, such as a revamp of the school’s social media strategy, gave him strong strategic thinking and leadership skills to put to use at General Mills. “It’s all about thinking about a problem, solving that problem and executing the solve,” he said.

Before accepting the job at General Mills, Kunysz considered several other states—Texas, Georgia, Ohio and California were all on the table. But Minneapolis was the one location that checked all his boxes. “There had to be major sports, a great food scene and a good network of young professionals, and Minneapolis has all of those,” he says. He loves the many lakes, parks and greenways, and he wasted no time purchasing an annual pass for Minnesota’s beautiful state park system. Just as appealing is a dining scene that’s high on quality but not necessarily on expense and long waits. “I can walk into a great restaurant and be seated in 20 minutes,” he says. “It’s an easy place to live.”

The Health Care Product Developer

Originally from Virginia, Kendall Bram, MBA’14, had very little in the way of expectations for Midwestern living when she moved to Minneapolis after earning her business degree. She joined a leadership development program at 3M, a huge science company with five business groups (including, yes, the consumer one, responsible for Scotch tape and Post-its). During the program, Bram worked on projects across the company as an internal consultant, giving her grounding in the range of industries where 3M operates. The diverse business landscape presented unique challenges, says Bram, “but Owen prepares you really well to embrace that ambiguity and find ways to contribute.”

Thanks to the leadership program, Bram has put down roots in Minneapolis with a group of friends already in place. Her network feels established and growing. Today as a global procedure marketer, she handles new product marketing in the health care business group, helping develop and bring to market new materials used in dental fillings and restorative procedures. The position requires Bram to communicate regularly with global teams, adapting to and interpreting a range of business practices and working styles. In navigating these worlds, she’s found her business school training invaluable.

“I looked to Owen to round out my knowledge of marketing and strategy, but also the core business competencies. It also opened the door to industries and businesses I hadn’t had exposure to,” she says. “I continue to take lessons from Owen on working with groups and how to influence and understand ambiguous business challenges.”

Bram cites Vanderbilt’s emphasis on collaboration as a particular boon. “A lot of that is represented here in my role, which is largely of a team nature, learning from the technical side of our organization and translating that knowledge to marketing to meet the needs of our customers,” she says. Bram notes that her training in how to influence others has also come in handy.

Echoing Rosario and Kunysz, Bram has found much to love about her adopted city. Living in the downtown neighborhood of the North Loop, she enjoys easy access to paths and green spaces along the Mississippi River, as well as plenty of nearby coffee shops and restaurants. No ice fishing yet—but Bram has dabbled in some cross-country skiing. “I hadn’t done much winter stuff before,” she says. “People here are really into the outdoors.”

The Mission-Driven Manager

Miller wasn’t new to the medical world when she started at Vanderbilt. She had worked as a medical device sales representative for many years but realized she’d need an MBA to move ahead. When she heard that Vanderbilt offered a dual master’s in marketing, strategy and theology through Vanderbilt’s Owen School and Divinity School, she was all in.

While in graduate school, Miller attended the National Black MBA Association Conference, where she received introductions to the major Fortune 500 companies that would be recruiting a few months later. “You needed to show up and be ready to stand out, and I feel like Owen prepared us for that with our elevator pitch,” she recalls. “They made sure we knew what it meant to have executive presence. They also did a great job of preparing us to translate the classroom work we were doing into the career we wanted to create.”

Much like Bram at 3M, Miller learned the ropes at Medtronic through an 18-month leadership development program, which placed her on projects in Minneapolis and Washington, D.C. Today, she leads marketing strategy for the company’s U.S. region. “From a mission perspective, it goes far beyond the development of products,” Miller says. “It ensures that patients have access to those products. Regardless of how hard the problems are that we have to solve, when you realize that the impact of your work actually saved someone’s life, that makes it worth it.”

For Miller, whose work is all about achieving better health and health care equity, Minneapolis is an ideal home in many ways. “It’s one of the healthiest cities in the United States,” she says.

The Banker

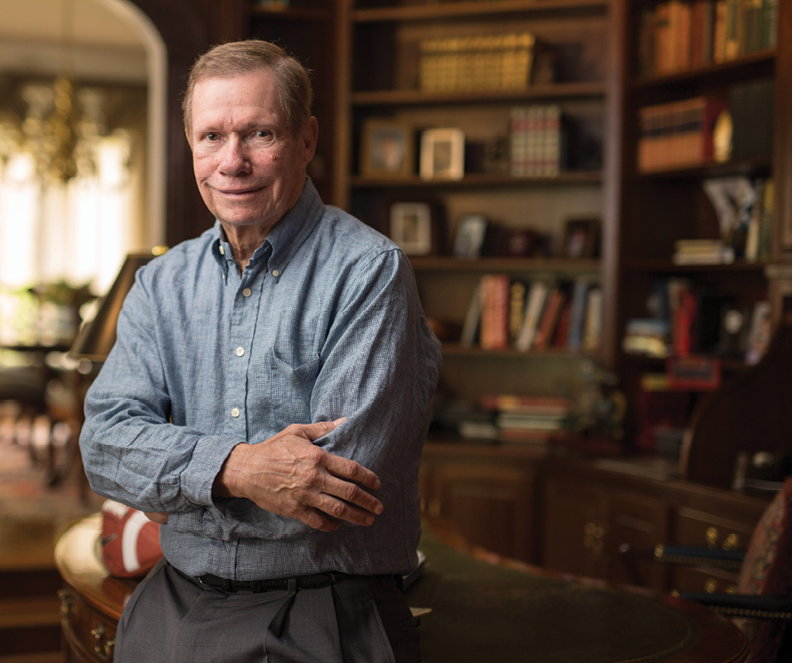

As a member of the Owen School’s Alumni Board, Ben Reichenau, BA’92, MBA’97, sees a lot of freshly minted MBAs look southward to start their new careers. But he’s become a strong advocate for Minneapolis. “It has four seasons, and the people are nice, smart and friendly,” he says. Reichenau loves the “outdoor mindset” of the city and even plays platform tennis outdoors through the winter.

As a member of the Owen School’s Alumni Board, Ben Reichenau, BA’92, MBA’97, sees a lot of freshly minted MBAs look southward to start their new careers. But he’s become a strong advocate for Minneapolis. “It has four seasons, and the people are nice, smart and friendly,” he says. Reichenau loves the “outdoor mindset” of the city and even plays platform tennis outdoors through the winter.

Reichenau, who holds both his undergraduate and MBA degrees from Vanderbilt, has been at U.S. Bank since 2013 and in Minneapolis since 2014. Earlier in his career, he was a consultant with KPMG/BearingPoint and Ernst & Young and held leadership positions with Wells Fargo. At U.S. Bank, he works in wealth management with high net worth individuals. Reichenau’s team is in charge of developing strategy to build U.S. Bank’s base among these highly desirable customers, including products that fit their unique needs.

“Right now, customers can get everything they need from the bank, but it’s all siloed,” he says. “We want to deliver a unified experience for them throughout the branch.”

Reichenau credits the MBA program with teaching him how to solve problems by taking a holistic approach to business. “I look for answers across all fields,” he says.

Like Bram, he notes the importance of teamwork: “The team is so important, and you have to look at the reward system.” He also relies on the critical communication skills gained while pursuing his MBA at Vanderbilt. “Listening is a two-way activity,” he says. “You may feel like you’re getting something done in a meeting, but if you’re only talking and not listening, you are not solving problems.” ■