Market impact. It is part of the very fiber of Owen’s finance department. Members of the school’s finance faculty are not only contributing to the industry’s intellectual underpinnings and analytical tools but also training students who, as Vanderbilt alumni, are putting theory into practice worldwide. We look here at some of the key players who are helping shape the face of modern financial management.

Market impact. It is part of the very fiber of Owen’s finance department. Members of the school’s finance faculty are not only contributing to the industry’s intellectual underpinnings and analytical tools but also training students who, as Vanderbilt alumni, are putting theory into practice worldwide. We look here at some of the key players who are helping shape the face of modern financial management.

At the Center of Research

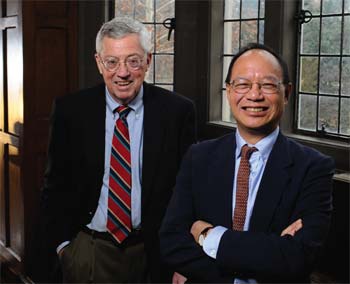

The sweep of history represented by the finance faculty is nowhere more dramatically represented than in the Financial Markets Research Center (FMRC). Founded in 1987 to foster research in financial markets, instruments and institutions, it has long promoted interaction among executives, researchers and the Owen faculty, particularly through its renowned annual conference. Hans Stoll, the Anne Marie and Thomas B. Walker Jr. Professor of Finance and Director of the FMRC, calls the center “our window on the real world and our connection to what’s going on and the issues that face policymakers and financial executives.”

Stoll is known for developing put-call parity and for seminal work in market microstructure, which has become a major subfield within finance. He is also credited with providing analysis that demystified the role of futures in the crash of 1987, leading to a more balanced approach to regulation amid calls for drastic measures. The breadth and depth of his work have earned him one of the industry’s most stellar reputations—he has been elected President of both the American Finance Association and the Western Finance Association—and the markets still bear the stamp of his contributions.

Tom Ho, who has worked with Stoll since they co-authored papers at the Wharton School in the late ’70s, serves as the FMRC Research Professor of Finance. Through voluminous research, papers and books, Ho has been key to introducing rigorous mathematical modeling to securities. His work with the Thomas Ho Company, providing analysis and consulting to financial institutions, is an example of the integration between Vanderbilt finance research and the business world. It also demonstrates how the FMRC is bringing together all the elements of financial education, research, practice and policymaking.

Watch Stoll’s video about the FMRC.

Academic Firepower

The huge impact Owen has had on the world of finance grows larger this year with the introduction of NASDAQ OMX Group’s Alpha Indexes. Developed by Bob Whaley, the Valere Blair Potter Professor of Management, and Jacob Sagi, the Vanderbilt Financial Markets Research Center Associate Professor of Finance, the indexes help investors isolate the performance of individual stocks or commodities from broader shifts in exchange-related funds. This will, according to Sagi, “allow investors to understand correlations better and allow for interesting hedging opportunities.”

The idea for the indexes started when alumnus Eric Noll, MBA’90, who serves as NASDAQ OMX Group’s Executive Vice President of Transaction Services, turned to what he calls the “academic firepower” of Whaley and Sagi for help in developing new NASDAQ products. Noll was looking for something of the caliber of the Market Volatility Index (VIX), or “Fear Index,” created by Whaley for the Chicago Board Options Exchange in the early ’90s. The VIX, which quantifies the market’s expectation of short-term volatility, has become a highly influential measure; a futures contract based on it has traded publicly since 2004. Sagi, an expert on asset pricing and decision theory with wide-ranging research and practical interests, has conducted research with Whaley on relative performance indexes.

The NASDAQ OMX Group is offering derivatives of the indexes that will allow investors—primarily institutional at first—to bet on or guard against fluctuations in the worth of securities or funds. The products are designed to help investors hedge against the kind of market swings exemplified by last year’s “flash crash.” The collaboration between Vanderbilt and NASDAQ is, Sagi says, “the kind of thing that demonstrates how you can take research-based knowledge and apply it in a way that helps people and brings value to the market.”

Read more about Whaley and Sagi’s research.

Watch Sagi’s video about the creation of the NASDAQ indexes.

Wellspring of Knowledge

As veterans on the finance faculty, Professors Bill Christie, Nick Bollen and David Parsley represent a wellspring of theoretical and applied knowledge, transmitting real-world experience and academic rigor to the classroom. Their accomplishments are among the school’s most noteworthy.

Christie, the Frances Hampton Currey Professor of Finance, analyzed NASDAQ pricing in the ’90s and found that market makers were implicitly colluding to maintain artificially high trading profits at the expense of investors. His research led to sweeping reform of the NASDAQ market, the introduction of the SEC Order Handling Rules and a billion-dollar settlement. Christie also served as Dean of the Owen School from 2000 to 2004.

Bollen, the E. Bronson Ingram Professor in Finance, authored a cutting-edge 2008 study of hedge fund liquidity that quantified the risks to investors facing the restriction or suspension of withdrawals from hedge funds during market turmoil. The subsequent financial crisis bore out his conclusions, as many funds closed and others were revealed to be fraudulent. His most recent research focuses on predicting which funds are at a higher risk of fraud by examining their statistical footprints for peculiarities best explained by misreporting.

Parsley, the E. Bronson Ingram Professor in Economics and Finance, has shown through his research into political connections and lobbying that the portfolios of firms with higher lobbying intensities and expenses outperform those of firms without such connections. He also has discovered that politically connected firms appear to be less sensitive to market pressures to increase the quality of financial information given to minority shareholders. His current work includes seeking explanations for the globally declining impact of exchange rates on prices.

Watch Christie’s video about the real-world consequences of research.

Watch Bollen’s video about the study of hedge funds.

Watch Parsley’s video about the world economy.

Emerging Ideas

The Owen finance faculty’s reputation continues to grow thanks to newer members like Alexei Ovtchinnikov and Miguel Palacios, both Assistant Professors of Finance. Ovtchinnikov has done widely cited work on corporate political contributions, showing in a large-scale study published in The Journal of Finance that there is a positive and significant relationship between such donations and both stock returns and return on equity. His follow-up study examined the nature and effectiveness of individual contributions, particularly to politicians with oversight of industries having economic impact on contributors. Ovtchinnikov is now looking at the flip side of the coin, studying the way government policy affects corporate decision-making.

Palacios’ work on human capital, its quantification and its effect on other assets’ prices, is decidedly and excitingly off the beaten path. One question he raises is what effect the retirement of baby boomers, who will no longer have future earnings as an asset, will have on the value of stocks. Another is the possibility of a financial instrument tied to future earnings, and whether such an instrument “might make people willing to take more risks in stocks and other investments, changing their price and return,” he says. He and a business partner have explored the practical aspects of his questions for the last nine years, founding a company called Lumni Inc., which pays for the education of young adults—many who could not afford college otherwise—in exchange for a small stake in their future earnings. His book Investing in Human Capital: A Capital Markets Approach to Student Funding was published by Cambridge University Press in 2007.

Read more about Ovtchinnikov’s research.

Read more about Palacios’ research.

Watch Ovtchinnikov’s video about political donations.

Watch Palacios’ video about the value of human capital.

Steering a New Course

Australian-born Kate Barraclough jumped at the chance to take a more active role in oversight of the school’s Master of Finance (MSF) program. As its Director, she says, “I see myself as taking an already excellent product and raising its profile by engaging and coordinating its stakeholders—faculty, alumni, employers and current and future students. My aim is to build a great program, recognized as one of the best in the country.”

Her background is yet another example of the way in which research, teaching and real-world experience come together within the Owen faculty. A former manager at KPMG Canberra and financial consultant to the Australian government, she has research interests that include asset pricing, derivatives and bond markets. Under her guidance, MSF has introduced a new course on financial modeling (which she teaches), formed a board of advisers made up of distinguished alumni and friends of the school, and created an internship program for the MS Finance Class of 2012. The latter was an initiative proposed by alumnus Bruce Heyman, BA’79, MBA’80, who is Managing Director and Partner at Goldman Sachs in Chicago and a member of Owen’s Board of Visitors.

Barraclough is working to encourage cohesion within the MSF group with a number of MSF-only classes. “A key part of my role is mentoring our students, encouraging and supporting them while they are at Owen,” she says. “Seeing them grow through their experiences at Owen is extremely rewarding for me.”

Wall Street Presence

It would be difficult to overstate the Vanderbilt presence in the world of business and finance. Thousands of graduates carry the lessons learned here into boardrooms, exchanges and regulatory offices worldwide. One notable example is Sean Rogers, BA’87, MBA’95, a key figure in one of the two largest financial institutions on Wall Street.

Rogers serves as Managing Director at Bank of America, overseeing communications technology. He works closely with senior management at companies like Nokia, Ericsson and Motorola, advising them on an array of financial matters, including capital formation and structure, corporate finance, mergers and acquisitions, joint ventures and IPOs. It is a job that requires wide-ranging knowledge applied to complex but specific situations in real time, and he cites his increasing appreciation of the “softer skills” he learned at Owen.

“It’s learning how to study,” he says, “how to work in teams, how to communicate with your counterparts. As you become more senior in investment banking, what makes someone good or bad comes down to qualitative skills. You’re more concerned with building relationships, with understanding issues. You become results-oriented.”

More and more, those relationships transcend borders and backgrounds. “That’s why both the student mix and the interdisciplinary possibilities at Owen, like those with the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, are so valuable,” he says. He also cites the class size and the close relationships he was able to develop with both students and professors. He has long since been returning the favor, bringing his business expertise to Owen as a member of its Board of Visitors—something that is particularly important in that Bank of America has become the single biggest recruiter of Owen grads.

Tools of the Trade

Vikas Dwivedi, MBA’00, says his career has become “all energy, all the time.” After stints at Shell Oil, Enron, Prudential Equity Group and Morgan Stanley, and a rating as No. 1 stock picker in electric utilities in 2004, he is bringing his experience in energy and commodity trading, private equity, project development, operations and engineering to bear on his own firms. He is a Principal at BTU Capital Management, a Houston-based hedge fund focused squarely on energy, and Quantum Energy Partners, a $5 billion private equity firm.

“It’s focused on natural gas,” he says of BTU, “and our trades will allocate capital directly into futures and options on the commodity itself.” He came to Owen as an engineer and an energy trader, but says, “I didn’t have any real sense for the broader capital markets and the bigger world. Seeing how those markets work and how they impact each other and impact energy was very helpful. It gave me a much bigger perspective on how stuff is really put together. And not having a financial background, it was a really good rounding experience to learn accounting and a little more on corporate valuation.”

In addressing students and recent graduates, he encourages creativity and daring. “Never assume everything’s been solved,” he says. “There are always other markets and other problems if you can help solve or even identify them. I’d also recommend a bit of irreverence for the way markets work. They’re not perfect. See if you can insert yourself into something that’s not quite right, which is always an opportunity.”

Four years ago Christopher Parks found himself facing an all-too-common dilemma. He and his mother, who was in the midst of cancer treatments, were sitting in her living room going through a stack of her medical bills and those of his father, who had died recently.

Four years ago Christopher Parks found himself facing an all-too-common dilemma. He and his mother, who was in the midst of cancer treatments, were sitting in her living room going through a stack of her medical bills and those of his father, who had died recently.

Ray Sumner, MBA’10, woke up in a bed with white sheets. He recognized his mother, who was holding his right hand. She had traveled from their family farm on Staten Island to keep vigil at his bedside in Bethesda Naval Hospital.

Ray Sumner, MBA’10, woke up in a bed with white sheets. He recognized his mother, who was holding his right hand. She had traveled from their family farm on Staten Island to keep vigil at his bedside in Bethesda Naval Hospital.

Academics often like to talk about providing “real-world experience” for their students, but the real estate program at the Owen School has ventured beyond the standard rhetoric.

Academics often like to talk about providing “real-world experience” for their students, but the real estate program at the Owen School has ventured beyond the standard rhetoric. Building a program

Building a program