Sharran Srivatsaa, MBA’08, remembers arriving in Tupelo, Miss., well after dark and encountering what most people would expect to see on a small-town Thursday night: very little. “There wasn’t much going on.”

In the morning he saw the place, physically and figuratively, in an entirely different light, as through an arrival-in-Oz transformation when suddenly the picture turns from black and white into spectacular color. “When we woke up, suddenly it was a hub of activity—an amazing difference. We were told that, on weekdays, Tupelo swells from about 40,000 to more than 100,000. It really pulls workers in from the neighboring counties.”

Put another way, more people come into Tupelo each day to work than come in an entire year to see the city’s most famous attraction, the two-room house where Elvis Presley was born.

Well before Toyota chose Tupelo over many rival suitors as the site of a huge new manufacturing plant (set to open in 2010), the town would have been an economic wonder in any place, by any standard. But especially given this town’s location, visitors could be forgiven for saying, “I don’t think we’re in Northeast Mississippi anymore.”

A Fateful Phone Call

A Fateful Phone Call

Before his graduation in May, Srivatsaa was one of the leaders of Project Pyramid—a two-year-old, student-driven initiative aimed at alleviating global poverty. The interdisciplinary project includes students from Owen, Vanderbilt Law School, Divinity School, Peabody College, School of Medicine, the Graduate Program in Economic Development (GPED), and College of Arts and Science. As part of their work, participants have traveled to such distant locales as India and Bangladesh, where they met with Nobel Peace Prize winner and GPED alumnus Muhammad Yunus, PhD’71. But it was only through a chance conversation that they managed to visit the economic miracle barely four hours away from Nashville.

Actually, says Srivatsaa, the group had wanted to put together a trip to a spot within manageable driving distance from Vanderbilt. “We had international trips, and we had a lot of international students who had seen poverty in other countries. We had a lot of domestic students who wanted to do something closer to home.”

So he approached Bart Victor, the Cal Turner Professor of Moral Leadership and faculty adviser to Project Pyramid. Knowing the town had a history of remarkable economic development, Victor recommended Tupelo.

There the process halted. “I didn’t know anyone in Tupelo who could help us put a trip together,” says Srivatsaa, who now works in private wealth management for the Atlanta office of Goldman Sachs. Then, by chance, as he was making thank-you calls on Owen’s behalf to a list of donors, he saw the name of Scott Reed, BA’80, and a Tupelo address beside it.

Reed is part of what is surely the family with the deepest Vanderbilt ties in Tupelo, maybe even in all Mississippi. His father, Jack Reed Sr., BA’47, and two uncles graduated from Vanderbilt after World War II. Scott’s brother, Jack Jr., BA’73, and sister, Camille, BA’75, were there in the ’70s. Jack Jr. met his wife, Lisa, BA’74, at Vanderbilt. Lisa’s parents had met there, too. Enough Reed nephews and cousins have matriculated to Nashville that Scott has to think before naming a number.

Scott never actually attended Owen. Just after he was accepted in 1985, he says, he jumped at a chance to start the first full-service brokerage firm in northern Mississippi. But he contributes financially. “One of the things I like about Vanderbilt,” he says, “is that, when they call about giving, they have students call. You can keep up with what’s going on at the school.”

During their conversation Srivatsaa made a point of bringing up Project Pyramid and its goal of eradicating global poverty (“You’d think they’d get a bigger goal,” Scott chuckles) and asking whether Scott could facilitate a contact for them. And, as it happened, Scott knew just the person: his brother Jack, who was chairman of Tupelo’s renowned Community Development Foundation. (Lesson: There is always a Vanderbilt connection.)

In April Professor Victor and eight Project Pyramid students—three from Owen, three from GPED, and two from the Divinity School—rented a large van and drove to Mississippi to learn “the Tupelo Story” firsthand. During their visit the group first met with representatives of the Community Development Foundation. They toured the plant of a Tier 1 automotive supplier and visited two of the nine industrial parks that the city had farsightedly developed on land it had purchased. Over lunch with the local Vanderbilt Liaison Group—the Reed brothers; their father, Jack Sr.; local businessman Henry Dodge; and city attorney Guy Mitchell—they talked about what they had learned.

“This one-day trip,” wrote GPED student Sait Mboob “was arguably the best lesson I’ve had in six years of studying economic development.”

It was such a good lesson, in fact, that later in the spring, all 60 students in Vanderbilt’s GPED program went to Tupelo. Another Project Pyramid team will return next year. And the students are busily analyzing how to apply the lessons of Tupelo to other settings in the United States and around the world.

Rethinking Stereotypes

To learn the Tupelo Story, you must be prepared to unlearn what you thought you knew about Mississippi: all the stereotypes; all the “lasts” in education and health; the intractable poverty; the antebellum attitudes that led William Faulkner to write that, here, “the past isn’t over; it isn’t even past.”

In Tupelo everything has long been about building for the future. From practically nothing they built the capacity for bringing new businesses to the area, in ways that created both jobs and sustainable revenues for further public investments. The result is a diverse local economy that has remained remarkably stable.

Through planning and cooperation they established one of the best public school systems anywhere. Half the elementary schools have earned national blue-ribbon status. Twice, Tupelo High has received the U.S. Department of Education’s Excellence in Education Award. Public investment—highest, per pupil, in the state—has given Tupelo schools a student-teacher ratio of 13 to 1. Graduation rates not only are among the highest in Mississippi; they’re 18 percentage points better than the national average. There is virtually no “white flight”; 98 percent of the town’s school-aged children attend public schools.

North Mississippi Medical Center, which serves a 22-county area and ranks as the largest nonmetropolitan hospital in the nation, won the prestigious Baldrige Award for quality this year. (Many of its 430 doctors are Vanderbilt-trained, brags Jack Reed Jr.)

For years the town has drawn workers from across northern Mississippi and industries from around the country. And that was before Toyota announced that it had chosen Tupelo over a number of rival suitors for a huge new North American manufacturing plant.

The joke, told not so jokingly by locals, is that if Presley were growing up in Tupelo today, he wouldn’t leave. Indeed, one striking fact about Tupelo is the number of its sons and daughters who go away to college, like the Reeds and their children, and return to continue building the community.

A Resurgence Rooted in Tragedy

Things weren’t always so rosy. “In the 1930s,” says Scott Reed, “we were one of the poorest counties in the poorest state in the Union. I think Project Pyramid’s interest was in how we overcame that legacy. It’s like the way my dad was teasing an old friend of his: ‘Junior, are you ever going to amount to anything?’ And he replied, ‘Well, if you saw where I came from, you’d be more impressed.’”

What’s in a Name?

By Randy Horick

Project Pyramid draws its name from a book by C.K. Prahlad, The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, and its central idea that businesses can operate profitably in impoverished areas of the world while contributing to the development and well-being of those who live there.

In Owen’s characteristically make-it-happen fashion, students drove the development of the project: an interdisciplinary, collaborative effort that would draw participants from Vanderbilt’s professional schools and undergraduate community. It would involve both education and sustained action to help alleviate global poverty. Dean Jim Bradford not only approved the project but empowered the students to take a shaping role, even in designing a course on the subject. Victor remembers that Bradford sat in on the initial class and sent him a text message even before the session was over: “These kids are different.”

It’s true, Victor says. “They’re not just contemplative. They want to change the world. In my experience, I’ve never seen this degree of commitment from students on these issues.”

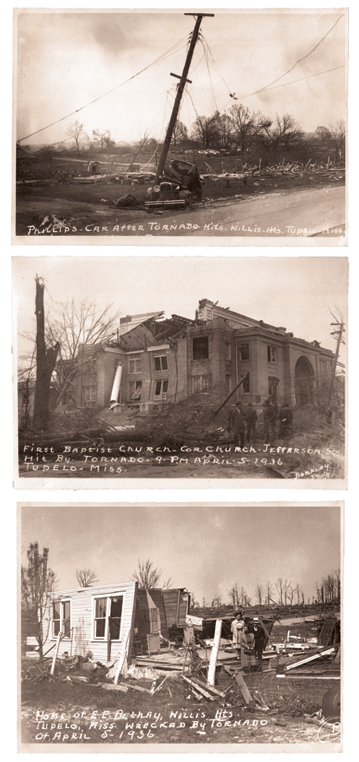

The Reed brothers will tell you that Tupelo’s resurgence was rooted in tragedy. In 1936 a monster tornado killed more than 200 people and left the place in ruins. But the tornado also marked a turning point of sorts. “We had to start over and work together to make things happen,” Scott says. “It was the beginning of what we came to call the Tupelo Spirit.”

Jack Reed Jr. also points to the fortuitous presence of “some enlightened business leadership”—particularly a newspaper editor named George McLean. Starting the Community Development Foundation was his idea, and he won the support of other leaders in the business community, including the Reeds’ father, Jack Sr.

“McLean was trained as a Presbyterian minister and had a really strong sense of social justice—that we’re all in this together and have to help each other,” Jack says. “Tupelo has an egalitarian ethic and a reputation for inclusiveness.” McLean, believes Jack, helped cultivate that civic sensibility.

Early on, civic leaders agreed that a key to development—one that ultimately proved crucial in Toyota’s decision—was a strong system of public education. The leaders pledged to send their children to public schools. And they formed one of the nation’s first private foundations to raise money for those schools—one of many public-private partnerships.

Community leaders were just as deliberate about laying the groundwork for success in other areas, too. Years ago, for example, they put together a “thoroughfare committee” to ensure that Tupelo would have the transportation corridors it needed. As a reflection of the town’s egalitarianism, Scott says, it wasn’t unusual to see millworkers and the chair of the CDF on committees together.

In the 1960s the Community Development Foundation bought up big tracts of land outside the town limits that would eventually serve as industrial parks. Now the city leases the properties to companies that relocate to Tupelo, then plows the proceeds back into the community.

What seemed to impress the Vanderbilt visitors most was the all-for-one spirit for which the Reeds themselves served as exemplars. The family, notes Victor, owns a century-old clothing business, the largest in town. But they actively solicited big-box competitors like Wal-Mart to enter the local market—a strategy that runs counter to what students traditionally learn in business school.

“I was surprised by how intrigued the students seemed to be with that,” says Scott Reed. “It didn’t seem like rocket science. There was an understanding that, if the community thrives, we’re going to thrive with it.”

If the strategy hindered the Reeds’ business, it doesn’t show. Along with two locations in Tupelo, the family also operates stores in Starkville and Columbus, Miss. “We’re a ring, not a chain,” laughs Jack Jr.

Partnering for the Future

The business lessons from Tupelo have not been lost on the newer generation of Vanderbilt students intent on changing not just their corner of the world but the whole global village. “Tupelo can be a story of inspiration,” says Sharran. “They have an amazing interaction between public and private enterprise. The CDF straddles that line. Private organizations just cannot do it all.

“They have a lot to teach us: Take a long-term view, and lay a foundation for our children and their children so the community can develop and grow. They had projects lined up 30 or 40 years out. Yet a vision is not enough. Selflessness is what guided that community.”

Says Scott Reed: “I think the students’ biggest takeaway is that there’s nothing we’re doing that others can’t do. If you figure out how to replicate this model, you can make strides for eliminating poverty.”

One day was more than enough to energize the group into thinking about opportunities Tupelo might offer. One possibility, suggests Srivatsaa, is a cross-disciplinary academic case study of Tupelo’s development. “Project Pyramid is perfect for that because no other organization encompasses so many disciplines across the university. Peabody students could study the educational system. Medical students could study the health care system. There’s a strong tie between every area of Tupelo and every area within our group.

“We have something spectacular in our own backyard with a strong Vanderbilt connection that needs to be nurtured.”

“I’m really excited about creating a more formal partnership with Vanderbilt so we can have the input of these really bright young people coming in here every year,” says Jack Reed Jr. “It certainly is a win/win.”

Meanwhile, Tupelo is becoming more integral to the work of Project Pyramid. Vanderbilt Professor of Economics James Foster—who, says MBA student Ryan Igleheart, “knows more about Tupelo than anyone at Vanderbilt”—has discussed teaching a Project Pyramid-related course at Owen in the future. For the first time, there will be short courses about Project Pyramid at the Divinity and Law schools. Igleheart, who serves as President of Project Pyramid, will lead a second group from Vanderbilt to observe and learn in Tupelo. “Our next step,” he says, “is to adapt their model to other places.”

Those places may include Bangladesh, where, building on previous Project Pyramid efforts, Vanderbilt students will return in December and again next spring to work on a model village concept. They also could include Mozambique, where Project Pyramid participants may explore economic development strategies with Vanderbilt’s Institute for Global Health, which operates 10 AIDS clinics in the country.

The lessons of Tupelo also may reach to other business schools. Last fall Owen hosted a first-of-its-kind case competition on poverty alleviation. Teams from 35 schools, including Wharton, Chicago and Yale, participated. It’s part of an effort to plant seeds that could grow into Project Pyramid groups elsewhere. “The teams really started to embrace the excitement and energy of this project,” says Igleheart. Every week he receives e-mail messages from people around the world interested in getting involved. Which reminds him: Among growing numbers of tasks on Project Pyramid’s to-do list is a white paper on how to help others get started.

It’s the ripple effect, says Igleheart, that Project Pyramid has always intended to create. Ask students who have been part of it, and they’ll tell you those ripples have become strong currents in their own lives. Even after graduation Srivatsaa remains involved in building an advisory board of community leaders.

Igleheart, who is pursuing a Health Care MBA, says, “A big part of me wants to make this the focal point of my business career.” It’s a commonly heard sentiment—a reflection, perhaps, of a generational change and, perhaps also, of how Tupelo is a generation ahead of the curve. “There’s a point at which we’re all connected,” says Igleheart. “As a global community we have to succeed together. The world is waking up to that.”

Comments

3 responses to “A Town Transformed”

A great post, very informative and graphic. To be honest i have never heard of ‘Tupelo’ until today! Thanks

Great to see towns like Tupelo benefiting from business! I think the short courses about Project Pyramid will be great to attend.

Interesting in the way streotypes change and things are being rebuilt.