Vanderbilt’s finance and business economics faculty have deep roots among the best minds in international policy, and they continue to carry the torch today, fully grounded in theory and deeply connected to the dealings of everyday business.

Just five years after the Vanderbilt Owen Graduate School of Management opened its doors, acting dean James V. Davis hired a former U.S. Federal Reserve Board governor and widely respected expert on monetary policy named J. Dewey Daane. Though Daane, who died in January 2017 at the age of 99, came to Nashville with the intention of splitting his (43-year) retirement between Vanderbilt and Commerce Union Bank, his presence immediately helped establish the new business school’s reputation in Washington policy circles.

Just five years after the Vanderbilt Owen Graduate School of Management opened its doors, acting dean James V. Davis hired a former U.S. Federal Reserve Board governor and widely respected expert on monetary policy named J. Dewey Daane. Though Daane, who died in January 2017 at the age of 99, came to Nashville with the intention of splitting his (43-year) retirement between Vanderbilt and Commerce Union Bank, his presence immediately helped establish the new business school’s reputation in Washington policy circles.

Today, those connections remain strong as several current members of the Vanderbilt business school’s faculty have served in top roles for agencies like the Federal Trade Commission, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Reserve. In addition to informing their academic research, students, alumni and private industry alike all benefit from these faculty members’ policy expertise.

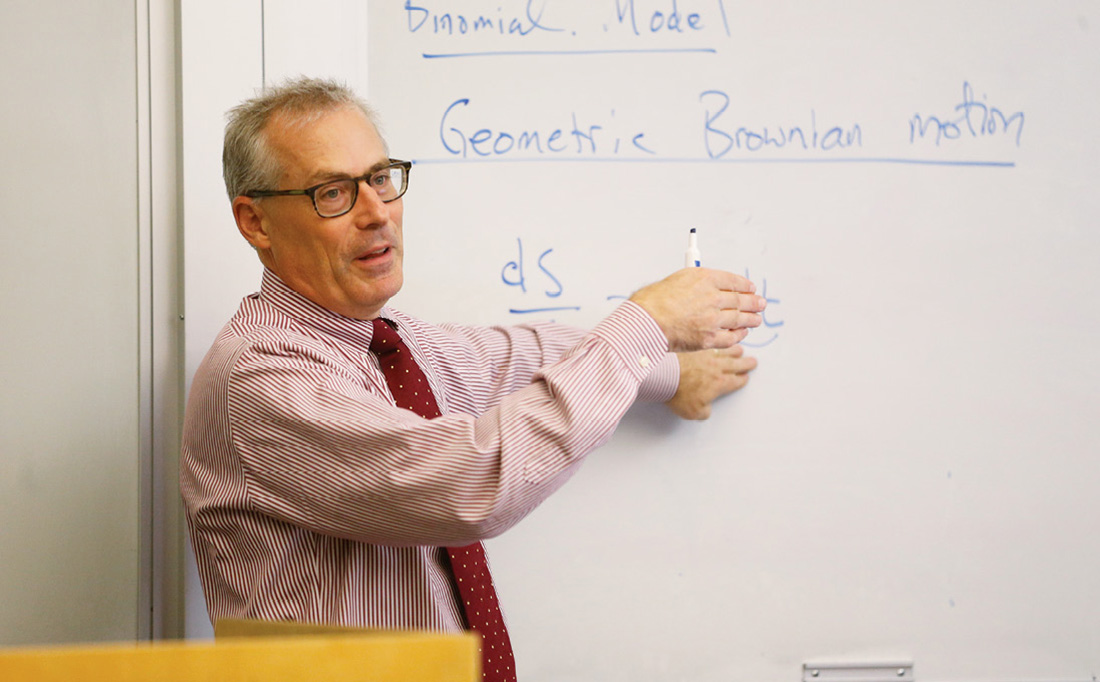

David Parsley, E. Bronson Ingram Professor of Economics and Finance, and a veteran of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, the International Monetary Fund and the South African Reserve Bank, among others, has assumed Daane’s monetary policy legacy most directly. In the last few years, Parsley has taken over one of Daane’s longstanding classes that regularly brought Washington speakers such as former Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker and former vice chairman Donald Kohn to campus. Other guest speakers have included the executive vice president of the American Bankers’ Association and the chief economist of the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Students not only hear from these influential leaders, but typically participate in a robust question-and-answer session. “Students love this class,” Parsley says. “And the speakers say they love it, too.”

More recently, Parsley has begun traveling with a group of students each year to meet with top industry and policy leaders in Washington, D.C. The trips include stops at the World Bank, the IMF and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve system. “When we go visit Janet Yellen and the Board of Governors, we actually meet her in the room where the [Fed] holds its policy meetings,” he adds. “It’s a spectacular room, and addressing one of the most powerful women on the planet is a great opportunity.”

Also like Daane, Parsley has spent his career working on international monetary policy, focused primarily on the mechanics of exchange rates. “Once I got to the Fed, I was in the international section of the research department,” Parsley explains. “From that point, I haven’t gone back. Almost everything I’ve done has been international.”

Using big data to detect ‘cooked books’

When Craig Lewis, Madison S. Wigginton Professor of Finance, was tapped to become the chief economist at the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2011, he was also assigned another task: Create a new identity for the Division of Economic and Risk Analysis (formerly known as the Division of Risk, Strategy and Financial Innovation) that would fully embrace the potential for academic-style research to inform policymaking and enhance the SEC’s investor protection mandate. One transformational example is the enhanced role of data analytics to detect anomalous behavior by SEC registrants and filers.

In accepting the position with the SEC, Lewis saw an opportunity to translate his research interests into policy progress. He went into the job with an inkling that the data analytic tools that he and other researchers used could be adapted to spot “cooked books” and other signs of securities law violations. During his three-year stint at the SEC, he and his research colleagues developed an arsenal of smarter weapons for combating securities fraud. These include models that draw on hedge fund performance data to flag suspicious activity, quantitative analytic tools that identify anomalous financial reports, and even text analytic tools that parse the language of disclosure documents for telltale signs of fraud.

This novel approach has drawn praise from peers. An analysis in the CPA Journal described the work as initiating “a new era for the detection of accounting fraud and improper disclosure.” In short, the tools developed during Lewis’ time at the SEC allow regulators to catch more bad guys sooner, reducing risk in the market. Since returning to Vanderbilt in 2014, Lewis says his time at the SEC—and the connections made there—continue to guide his research interests. “You just learn a ton at a place like the SEC,” he says.

Like Parsley, Lewis also hosts policy leaders on campus to participate in his Financial Services Industry course. Panelists have included multiple acting and former commisioners from the SEC and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. “Thousands of people would pay big money to see a panel of these guys in D.C.,” Lewis says. “But here they are at Vanderbilt talking with a group of 25 students.”

Staying close to real-world issues

Antitrust expert Luke Froeb, William C. Oehmig Professor of Free Enterprise and Entrepreneurship, takes a different tack to his academic work: He lets real-world problems be his guide. As a former regulator and consultant, Froeb has examined countless antitrust cases. “Almost all of my research has been inspired by cases that I’ve worked on,” Froeb says. “The questions I try to answer are questions that real people are asking.” (A recent paper in the RAND Journal of Economics, for example, grew directly out of antitrust work on a parking company merger in 2007.)

Froeb’s research approach took root during the eight years he spent at the U.S. Department of Justice, beginning in 1986, where he served as one of the many economists tasked with reviewing mergers for their potential anticompetitive effects. But he was one of the first to develop tractable models that could predict how mergers would affect prices. Froeb’s models gave regulators a new method for analyzing mergers—one that soon became very popular. “After I left the DOJ for Vanderbilt,” Froeb explains, “people just started calling me asking, ‘Will you analyze this merger for us?’” And he often did. His models played a role in a variety of blockbuster mergers, from L’Oréal’s acquisition of Maybelline to Carnival’s purchase of Princess Cruises. When Froeb took a leave from Vanderbilt in 2003 to serve as the director of the Bureau of Economics for the FTC, he was tasked with developing guidelines for the agency’s now-frequent use of the merger models that he had helped develop.

Froeb’s focus on real-world problems provides the foundation for his unique approach to teaching. “I give students real-life situations starting from the first day of class,” he says. “My main goal is to teach them that economics is a tool that they can use to solve real problems.”

(Editor’s note: At press time, the DOJ announced that Froeb is now the deputy assistant attorney general in the antitrust division. He is currenty on leave from Vanderbilt.)

Another faculty member who relies on economics to solve real-world issues involving the intersection of policy and business is Mark Cohen, Justin Potter Professor of American Competitive Enterprise. “My whole interest in academia was doing policy-relevant research,” he says. “I wouldn’t be happy if I weren’t engaged in policy issues at some level.”

Cohen’s extensive experience includes roles as an economist at the Environmental Protection Agency, the FTC and the U.S. Sentencing Commission. In 2008, he was named vice president for research at Resources for the Future, a nonpartisan research institute focused on energy and environmental policy and staffed by Ph.D. economists. Cohen describes RFF as being “heavily involved in the economic analysis of proposed laws and regulations, and looking toward emerging issues and how we might go about tackling them.” For example, Cohen led a research team at RFF that advised the National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling. He returned to Vanderbilt in 2011 and continues his work at RFF as one of the organization’s research fellows.

Cohen says his scholarly research is often informed by his policy work, and vice versa. For instance, a recurring topic in Cohen’s scholarly work involves looking at “ways in which businesses take on what traditionally look like government roles when it is in their interest to do so.” One line of research in this area explores the extent to which disclosure requirements can prompt businesses to engage in a desired conduct, such as reducing emissions, more efficiently than direct regulation would. He traces his interest in this area back to his time at the EPA, where he observed, firsthand, the limits of conventional regulation.

CohenCohen says he can’t help bringing his varied policy experience into the classroom. “Having these kinds of experiences brings in war stories to students, brings in relevant research topics to the business school,” he says, “and helps me be a non-ivory-tower academic.”

Leave a Reply