Tag: fall2008

-

From Broadway to Wall Street

The MASIF club can trace its Wall Street roots back to Broadway. The musical never opened on Broadway, or anywhere else for that matter, and it probably never will. But in a way, the curtains haven’t yet dropped on The Party Girl. Though forgotten by many, the musical continues to make its impact known at the Owen School—just not in a way that you might suspect.

The year was 1977, and Max Adler, a prominent New York businessman, was sitting in his apartment on Fifth Avenue listening to another pitch. As one of the producers of the Tony Award-winning hit Annie, he was often being asked to finance other would-be Broadway musicals, like the one being described to him at that moment. This time, however, something held his attention. It wasn’t the script, which was about a U.S. senator and the mistress who runs his New York power base, or the fact that it was set to star veteran actor Robert Alda (Alan’s father) and an up-and-coming Dixie Carter. What interested him most was the person in front of him—the producer who had optioned the script. His name was Charles Doraine, MMgt’72, and it was his personal story that eventually convinced Max Adler to invest his money. Not in The Party Girl, that is, but in Vanderbilt.

“He said, ‘I don’t like the script, but I’m interested in you because you’re an entrepreneur,’” recalls Doraine. “I explained to him that I had graduated from Vanderbilt’s Graduate School of Management and that we thought of ourselves as managers of change. I told him we stood out because we looked at the world differently. Other schools were interested in people who would stay in the box, but GSM was looking for people who were outside of it.”

That “outside the box” line of thinking appealed to someone like Adler, whose path to success was anything but conventional. A bombardier in the U.S. Army Air Corps, he survived being shot down over the battlefields of Europe and imprisoned by the Nazis during World War II to return to civilian life in the late ’40s. Seeing an opportunity in America’s booming post-war economy, he started a mail-order business selling inexpensive gifts and gadgets. The catalogs were an immediate hit, and soon he expanded into other types of merchandise.

“He always sold these weird kinds of things, but one year he decided he would go into selling animals. He brought little burros across from Mexico, and they sold like fury and actually made the cover of Life magazine. It was amazing,” says Mimi Adler, Max’s widow.

While the burro-as-pet craze thankfully went away, Adler’s mail-order business did anything but. By the early ’60s the demand was so great for his merchandise that he decided to open his first retail store in New Jersey. Called Spencer Gifts, it caught on with customers and quickly drew the interest of Musical Corporation of America (MCA), a large music and television company based in California. Adler sold the business to MCA, which then took the brand nationwide. This windfall enabled Adler to dabble in other things that mattered to him, including Broadway shows like the one Charles Doraine had come to pitch.

But Adler was just as passionate about philanthropy, and when the conversation turned from The Party Girl to Vanderbilt GSM, he was eager to learn more about the school. Doraine agreed to put him in touch with Dean Samuel Richmond, thanked him for his time and went on his way, not realizing the importance of what had just occurred. It was only when Doraine got a phone call several years later that it dawned on him. A representative of the newly renamed Owen School was calling to invite him to a celebration honoring a donation given by Adler.

“Sometimes you can make a difference without even knowing it. I met Max just that one time, and look what happened,” Doraine says.

As it turns out, Max Adler had struck up a friendship with Dean Richmond during those intervening years and had grown so fond of the Owen School that he’d promised a significant sum for the construction of Management Hall. But before he could make good on that promise, Adler died unexpectedly in 1979. The donation that Doraine received the call about was actually given by Mimi in her late husband’s honor.

Mimi’s commitment to Owen, however, didn’t end there. In 1983 she donated an additional $25,000 to the school. The purpose of her gift was two-fold: First, she wanted the students to be able to learn how to manage money by making real-life investments, and second, she hoped the earnings from those investments would someday fund scholarships to the school. Mimi’s gift was named the Max Adler Student Investment Fund, or MASIF for short.

The student club responsible for managing MASIF is today one of the most popular at Owen. In 2007-2008, there were over 50 members, all of whom played a hand in deciding which stocks the club picked. Modeled after an S&P mid-cap index, the fund is divided into different sectors, such as real estate, health care, energy, and technology. Second years serve as the heads of these sectors, while first years act as analysts. Getting the first years involved in this manner was one of the initiatives of former MASIF President Nicholas Zager, MBA’08. Having worked at OppenheimerFunds prior to enrolling at Owen, Zager wanted to expose the club members to something akin to the real-world experience he’d had.

“When you set things up in a team-oriented and professional environment, you see certain people shine. Those of them who grab onto the idea of MASIF can really hit the ground running after graduation,” he says.

Zager’s other initiative as MASIF President was to fulfill Mimi Adler’s original vision by paying the first scholarship. In the 25 years since her donation, the fund had grown to well over $400,000 thanks to the students’ stock picks. With Dean Jim Bradford’s support and Mimi’s blessing, the MASIF club decided to sell off approximately half of that amount and create an endowment for the Max Adler Scholarship. The club members also set about determining the criteria that would be used to award the scholarship. It was agreed that the recipient should demonstrate not only leadership abilities and academic excellence but also a commitment to the school and a career in finance. In the end, several candidates were presented to Dean Bradford, and Bill Lambert, MBA’08, was chosen as the first recipient.

“I think MASIF offers a learning opportunity for people of all different backgrounds. It’s great to be able to pitch your thoughts on a specific stock to members, listen to their thought processes, and then measure those against your own. Not only does the fund create this atmosphere, but we then can act on these situations, and hopefully obtain market-beating returns for the fund in the process,” says Lambert.

Today Lambert is realizing his dream of working in corporate finance at Deutsche Bank AG in New York. His story is similar to those of other MASIF club members who have embarked on Wall Street careers. They all gained valuable experience managing the money that Mimi Adler gave to the Owen School in her late husband’s name. And whether they know it or not, they all owe a debt of gratitude to Charles Doraine and the musical that no one saw.

-

Q & A with Joyce Rothenberg

What services does the Career Management Center provide?

What services does the Career Management Center provide? The CMC does not play a traditional placement role in the sense of matching companies and students. Today’s MBA job market is all about fit, and that’s something only the companies and the students can assess; matchmaking is really not part of what we do. Our job is more about helping to develop the job market. Our role with corporate employers is to educate them about the school and to help them attract the talent that they need to run their companies. Our mission with students, on the other hand, is to help them prepare for their job search. It’s not just about finding an MBA job when they get out, although that’s really important to everyone. It’s also about giving them the tools that will allow them to seek jobs for the rest of their lives. We teach them how to pick a direction, match their skills to job requirements, fill gaps if they’ve got them, and then market themselves to companies.

The CMC does not play a traditional placement role in the sense of matching companies and students. Today’s MBA job market is all about fit, and that’s something only the companies and the students can assess; matchmaking is really not part of what we do. Our job is more about helping to develop the job market. Our role with corporate employers is to educate them about the school and to help them attract the talent that they need to run their companies. Our mission with students, on the other hand, is to help them prepare for their job search. It’s not just about finding an MBA job when they get out, although that’s really important to everyone. It’s also about giving them the tools that will allow them to seek jobs for the rest of their lives. We teach them how to pick a direction, match their skills to job requirements, fill gaps if they’ve got them, and then market themselves to companies. Does the CMC also provide career assistance for alumni?

Does the CMC also provide career assistance for alumni? Yes, there’s a person in my office named Debbie Clapper, who is the Associate Director of Executive and Alumni Career Services. She reviews resumes for alumni and consults with them in developing job-search strategies. For those who live in Nashville, she’s organized a job-seeking group that meets every other week. She’s also started taking her career services on the road to cities where there are larger concentrations of Owen grads. If any of our alumni are interested in career services, all they need to do is pick up the phone and call her. Or they can visit www.OwenConnect.com to find out more.

Yes, there’s a person in my office named Debbie Clapper, who is the Associate Director of Executive and Alumni Career Services. She reviews resumes for alumni and consults with them in developing job-search strategies. For those who live in Nashville, she’s organized a job-seeking group that meets every other week. She’s also started taking her career services on the road to cities where there are larger concentrations of Owen grads. If any of our alumni are interested in career services, all they need to do is pick up the phone and call her. Or they can visit www.OwenConnect.com to find out more. What advice do you give to students who are searching for jobs during these tough economic times?

What advice do you give to students who are searching for jobs during these tough economic times? Our students need to be a little more flexible about their searches. They also need to be persistent. There are jobs out there. They may not be the dream jobs that the students envisioned when coming to business school, but there are good MBA jobs. In certain sectors and regions of the country, the job market is quite robust. I think finding the right job is just a question of being realistic about what’s available and really matching your skills and interests to something that’s a good first step. Maybe you have to get two-thirds of the way to your dream versus the whole way when times are tough.

Our students need to be a little more flexible about their searches. They also need to be persistent. There are jobs out there. They may not be the dream jobs that the students envisioned when coming to business school, but there are good MBA jobs. In certain sectors and regions of the country, the job market is quite robust. I think finding the right job is just a question of being realistic about what’s available and really matching your skills and interests to something that’s a good first step. Maybe you have to get two-thirds of the way to your dream versus the whole way when times are tough. How can alumni play a part in the CMC’s success?

How can alumni play a part in the CMC’s success? We look for alumni to open doors for us at their companies. When we focus on companies we don’t know or the strategic holes in our employer relationships, we turn to alumni to make that connection either through the HR people who do the MBA hiring or through the senior managers who care about MBA talent. We always appreciate it when alumni make us aware of opportunities at their companies. Being an advocate for Owen is something that is really helpful and important to us.

We look for alumni to open doors for us at their companies. When we focus on companies we don’t know or the strategic holes in our employer relationships, we turn to alumni to make that connection either through the HR people who do the MBA hiring or through the senior managers who care about MBA talent. We always appreciate it when alumni make us aware of opportunities at their companies. Being an advocate for Owen is something that is really helpful and important to us. -

A Piece on Peace

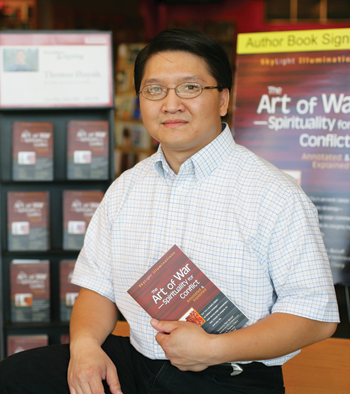

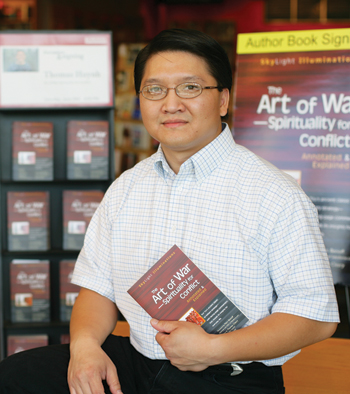

A 2,500-year-old text called The Art of War may strike some as an unlikely source of advice for today’s business leaders, but Thomas Huynh, EMBA’04, believes that there are valuable lessons to be learned from Sun Tzu’s masterpiece. Huynh has recently penned a new translation of the work, titled The Art of War: Spirituality for Conflict, with the hope that it will bring the Chinese general’s message to a wider audience.

A 2,500-year-old text called The Art of War may strike some as an unlikely source of advice for today’s business leaders, but Thomas Huynh, EMBA’04, believes that there are valuable lessons to be learned from Sun Tzu’s masterpiece. Huynh has recently penned a new translation of the work, titled The Art of War: Spirituality for Conflict, with the hope that it will bring the Chinese general’s message to a wider audience.Although the ancient document sounds as though it might glorify war, Huynh says it’s actually a treatise on peace, offering practical strategies for circumventing and diffusing conflict, whether on the battlefield, in the boardroom or at home. It is required reading for officers in the United States Marine Corps, as well as students at a number of B-schools, because of its innovative, still-relevant strategy for overcoming conflict. Marc Benioff, Chairman and CEO of Salesforce.com, who wrote the foreword to Huynh’s book, uses its classic principles to manage his company in an often hostile, highly competitive technology industry.

The text itself is a lesson in economy: 13 short chapters comprise The Art of War, but each is full of important lessons that teach the reader how to avoid conflict and resolve inevitable hostile situations using self-control, intelligence, courage and benevolence. Huynh’s annotations alongside the translation offer practical application of Sun Tzu’s philosophy.

Huynh enjoys a career in finance as Group Controller for Skyline Steel in Georgia, but has been dedicated to the study of Sun Tzu’s masterwork since he encountered the text as a teenager. In 1999 he launched Sonshi.com to provide Web space for authors, scholars and readers to gather and share information about Sun Tzu’s timeless approach to conflict resolution.

Says Huynh, “Conflict is part of life, but it is our response to the disagreement that has the greatest effect on our inner peace and personal happiness.”

-

An Investment in Experience

Dave and Liz Marchese Leverage. The power to get things done. That’s how Dave Marchese, BE’95, MBA’00, views his experience at Owen and his ability to switch careersfrom engineering to finance. Currently a Vice President at Haddington Ventures, a Houston-based private equity fund focused on the midstream energy sector, Marchese assists with deal sourcing, transactional work and portfolio company management. Prior to joining Haddington, he was Managing Partner at Eschelon Energy Partners, a company of similar ilk which he co-founded, as well as Reliant Energy, which was the launching pad for his industry changeover.

Marchese credits the late Elizabeth Powitzky, Owen’s beloved Associate Director of Admissions, for helping him shift his focus toward finance. Powitzky, who, sadly, lost her battle to breast cancer in 2001, steered him toward his summer internship at Reliant. “Elizabeth had a huge impact on my career change and helped me leverage my engineering experience and Vanderbilt MBA to get into energy finance,” he says.

His pre-MBA work with Jacobs Engineering translates into his current job, and he often draws on that knowledge in the development and construction of the energy infrastructure companies in Haddington’s portfolio. Additionally, he uses both his finance and engineering backgrounds to assist his wife, Liz, BA’95, in their development of a lakefront community, called The Point at Rock Island, on Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau.

Marchese chose Owen because of people like Powitzky, as well as the opportunity to work with high-quality students, and says he greatly benefited from the diverse professional backgrounds his classmates brought to the table.

“My previous experiences combined with the people I encountered at Owen have allowed for my current success.”

-

SIRIUS Business

If you are a SIRIUS Satellite Radio subscriber, then you are likely benefiting from savvy strategy developed by award-winning marketing veteran and Owen alumna, Vance LaVelle, EMBA’91. As a Senior Vice President, she is helping SIRIUS grow its subscriber base through service, sales and marketing. She also is helping the company prepare for its recently approved merger with XM Satellite Radio.

If you are a SIRIUS Satellite Radio subscriber, then you are likely benefiting from savvy strategy developed by award-winning marketing veteran and Owen alumna, Vance LaVelle, EMBA’91. As a Senior Vice President, she is helping SIRIUS grow its subscriber base through service, sales and marketing. She also is helping the company prepare for its recently approved merger with XM Satellite Radio.A quick glance at LaVelle’s bio shows a career path punctuated by a diverse range of experiences across a number of sectors, including technology, telecommunications, financial services, media and entertainment, and government, but the anchor throughout has been marketing.

Although she began her career at AT&T in operations, she has always been keenly interested in understanding consumers’ needs and building organizations around the experiences those consumers want to have. “I have always had good instincts about consumers and an ability to see the obvious path,” says LaVelle. Indeed, her marketing acumen has enabled her to successfully launch over 100 brands and turn the tide on flagging market shares and profits.

LaVelle’s instincts have been on point internally, too, in terms of recognizing when she has needed to change jobs, and she advises others to be aware of their own internal compasses. “We are the architects of our work life. We can be proactive or reactive, but regardless, change is inevitable.”

LaVelle has chosen the proactive path, joining SIRIUS after serving as Chief Marketing Officer with PNC Financial Services Group. She realized she was ready for a change, but after 10 months of exploring other options, including launching a consulting business, she also recognized her desire to get back into corporate life as an operator, not just an advisor.

She’ll no doubt continue to listen to her own internal cues, but for now, though, it’s SIRIUS business.

-

Banking Is in Her Blood

When asked what put her on the career path to her current position as CEO of Citizens First Bank in Bowling Green, Ky., Mary Cohron, EMBA’88, points to two pivotal factors: family and the Owen School.

When asked what put her on the career path to her current position as CEO of Citizens First Bank in Bowling Green, Ky., Mary Cohron, EMBA’88, points to two pivotal factors: family and the Owen School.Cohron’s predilection for banking comes naturally, by way of paternal DNA. Her father spent his life building a successful community bank in Glasgow, Ky., and she has fond memories of learning the business at his knee, from the ground up. But Cohron also credits Owen with shaping her career. “My MBA is the reason I was hired to run Citizens,” she says.

Interestingly, she did not receive a college degree prior to her graduate work at Vanderbilt. Cohron jokes about “the bad old days” when she was denied a scholarship at another university because her husband was already in dental school. Not one to let adversity hold her down, she worked her way up in a local bank and spent a number of years serving on the Bowling Green Board of Education and the Kentucky School Boards Association, as well as the bank board that would later spin off as the group of investors behind Citizens First.

Cohron made the decision to apply to Vanderbilt, having learned that some B-schools admit non-degree candidates. Her then-role as a Corporate Director made her an appealing candidate to the Executive MBA program, and after clearing a number of required high hurdles, she was admitted.

“Without doubt, Owen has enabled me to leverage my gifts and talents to their fullest potential.”

-

A Town Transformed

Srivatsaa Sharran Srivatsaa, MBA’08, remembers arriving in Tupelo, Miss., well after dark and encountering what most people would expect to see on a small-town Thursday night: very little. “There wasn’t much going on.”

In the morning he saw the place, physically and figuratively, in an entirely different light, as through an arrival-in-Oz transformation when suddenly the picture turns from black and white into spectacular color. “When we woke up, suddenly it was a hub of activity—an amazing difference. We were told that, on weekdays, Tupelo swells from about 40,000 to more than 100,000. It really pulls workers in from the neighboring counties.”

Put another way, more people come into Tupelo each day to work than come in an entire year to see the city’s most famous attraction, the two-room house where Elvis Presley was born.

Well before Toyota chose Tupelo over many rival suitors as the site of a huge new manufacturing plant (set to open in 2010), the town would have been an economic wonder in any place, by any standard. But especially given this town’s location, visitors could be forgiven for saying, “I don’t think we’re in Northeast Mississippi anymore.”

A Fateful Phone Call

A Fateful Phone CallBefore his graduation in May, Srivatsaa was one of the leaders of Project Pyramid—a two-year-old, student-driven initiative aimed at alleviating global poverty. The interdisciplinary project includes students from Owen, Vanderbilt Law School, Divinity School, Peabody College, School of Medicine, the Graduate Program in Economic Development (GPED), and College of Arts and Science. As part of their work, participants have traveled to such distant locales as India and Bangladesh, where they met with Nobel Peace Prize winner and GPED alumnus Muhammad Yunus, PhD’71. But it was only through a chance conversation that they managed to visit the economic miracle barely four hours away from Nashville.

Actually, says Srivatsaa, the group had wanted to put together a trip to a spot within manageable driving distance from Vanderbilt. “We had international trips, and we had a lot of international students who had seen poverty in other countries. We had a lot of domestic students who wanted to do something closer to home.”

So he approached Bart Victor, the Cal Turner Professor of Moral Leadership and faculty adviser to Project Pyramid. Knowing the town had a history of remarkable economic development, Victor recommended Tupelo.

There the process halted. “I didn’t know anyone in Tupelo who could help us put a trip together,” says Srivatsaa, who now works in private wealth management for the Atlanta office of Goldman Sachs. Then, by chance, as he was making thank-you calls on Owen’s behalf to a list of donors, he saw the name of Scott Reed, BA’80, and a Tupelo address beside it.

Reed is part of what is surely the family with the deepest Vanderbilt ties in Tupelo, maybe even in all Mississippi. His father, Jack Reed Sr., BA’47, and two uncles graduated from Vanderbilt after World War II. Scott’s brother, Jack Jr., BA’73, and sister, Camille, BA’75, were there in the ’70s. Jack Jr. met his wife, Lisa, BA’74, at Vanderbilt. Lisa’s parents had met there, too. Enough Reed nephews and cousins have matriculated to Nashville that Scott has to think before naming a number.

Scott never actually attended Owen. Just after he was accepted in 1985, he says, he jumped at a chance to start the first full-service brokerage firm in northern Mississippi. But he contributes financially. “One of the things I like about Vanderbilt,” he says, “is that, when they call about giving, they have students call. You can keep up with what’s going on at the school.”

During their conversation Srivatsaa made a point of bringing up Project Pyramid and its goal of eradicating global poverty (“You’d think they’d get a bigger goal,” Scott chuckles) and asking whether Scott could facilitate a contact for them. And, as it happened, Scott knew just the person: his brother Jack, who was chairman of Tupelo’s renowned Community Development Foundation. (Lesson: There is always a Vanderbilt connection.)

Scott Reed, left, and Jack Reed Sr. at the entrance to Tupelo’s historic Fairpark district. In April Professor Victor and eight Project Pyramid students—three from Owen, three from GPED, and two from the Divinity School—rented a large van and drove to Mississippi to learn “the Tupelo Story” firsthand. During their visit the group first met with representatives of the Community Development Foundation. They toured the plant of a Tier 1 automotive supplier and visited two of the nine industrial parks that the city had farsightedly developed on land it had purchased. Over lunch with the local Vanderbilt Liaison Group—the Reed brothers; their father, Jack Sr.; local businessman Henry Dodge; and city attorney Guy Mitchell—they talked about what they had learned.

“This one-day trip,” wrote GPED student Sait Mboob “was arguably the best lesson I’ve had in six years of studying economic development.”

It was such a good lesson, in fact, that later in the spring, all 60 students in Vanderbilt’s GPED program went to Tupelo. Another Project Pyramid team will return next year. And the students are busily analyzing how to apply the lessons of Tupelo to other settings in the United States and around the world.

Rethinking Stereotypes

To learn the Tupelo Story, you must be prepared to unlearn what you thought you knew about Mississippi: all the stereotypes; all the “lasts” in education and health; the intractable poverty; the antebellum attitudes that led William Faulkner to write that, here, “the past isn’t over; it isn’t even past.”

In Tupelo everything has long been about building for the future. From practically nothing they built the capacity for bringing new businesses to the area, in ways that created both jobs and sustainable revenues for further public investments. The result is a diverse local economy that has remained remarkably stable.

Toyota’s manufacturing plant is scheduled to open in Tupelo in 2010. Through planning and cooperation they established one of the best public school systems anywhere. Half the elementary schools have earned national blue-ribbon status. Twice, Tupelo High has received the U.S. Department of Education’s Excellence in Education Award. Public investment—highest, per pupil, in the state—has given Tupelo schools a student-teacher ratio of 13 to 1. Graduation rates not only are among the highest in Mississippi; they’re 18 percentage points better than the national average. There is virtually no “white flight”; 98 percent of the town’s school-aged children attend public schools.

North Mississippi Medical Center, which serves a 22-county area and ranks as the largest nonmetropolitan hospital in the nation, won the prestigious Baldrige Award for quality this year. (Many of its 430 doctors are Vanderbilt-trained, brags Jack Reed Jr.)

For years the town has drawn workers from across northern Mississippi and industries from around the country. And that was before Toyota announced that it had chosen Tupelo over a number of rival suitors for a huge new North American manufacturing plant.

The joke, told not so jokingly by locals, is that if Presley were growing up in Tupelo today, he wouldn’t leave. Indeed, one striking fact about Tupelo is the number of its sons and daughters who go away to college, like the Reeds and their children, and return to continue building the community.

A Resurgence Rooted in Tragedy

Things weren’t always so rosy. “In the 1930s,” says Scott Reed, “we were one of the poorest counties in the poorest state in the Union. I think Project Pyramid’s interest was in how we overcame that legacy. It’s like the way my dad was teasing an old friend of his: ‘Junior, are you ever going to amount to anything?’ And he replied, ‘Well, if you saw where I came from, you’d be more impressed.’”

What’s in a Name?

By Randy Horick

Project Pyramid draws its name from a book by C.K. Prahlad, The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, and its central idea that businesses can operate profitably in impoverished areas of the world while contributing to the development and well-being of those who live there.

In Owen’s characteristically make-it-happen fashion, students drove the development of the project: an interdisciplinary, collaborative effort that would draw participants from Vanderbilt’s professional schools and undergraduate community. It would involve both education and sustained action to help alleviate global poverty. Dean Jim Bradford not only approved the project but empowered the students to take a shaping role, even in designing a course on the subject. Victor remembers that Bradford sat in on the initial class and sent him a text message even before the session was over: “These kids are different.”

It’s true, Victor says. “They’re not just contemplative. They want to change the world. In my experience, I’ve never seen this degree of commitment from students on these issues.”

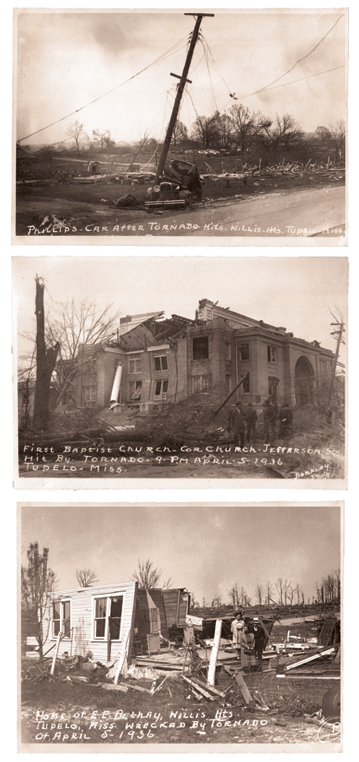

The Reed brothers will tell you that Tupelo’s resurgence was rooted in tragedy. In 1936 a monster tornado killed more than 200 people and left the place in ruins. But the tornado also marked a turning point of sorts. “We had to start over and work together to make things happen,” Scott says. “It was the beginning of what we came to call the Tupelo Spirit.”

Jack Reed Jr. also points to the fortuitous presence of “some enlightened business leadership”—particularly a newspaper editor named George McLean. Starting the Community Development Foundation was his idea, and he won the support of other leaders in the business community, including the Reeds’ father, Jack Sr.

“McLean was trained as a Presbyterian minister and had a really strong sense of social justice—that we’re all in this together and have to help each other,” Jack says. “Tupelo has an egalitarian ethic and a reputation for inclusiveness.” McLean, believes Jack, helped cultivate that civic sensibility.

Early on, civic leaders agreed that a key to development—one that ultimately proved crucial in Toyota’s decision—was a strong system of public education. The leaders pledged to send their children to public schools. And they formed one of the nation’s first private foundations to raise money for those schools—one of many public-private partnerships.

Community leaders were just as deliberate about laying the groundwork for success in other areas, too. Years ago, for example, they put together a “thoroughfare committee” to ensure that Tupelo would have the transportation corridors it needed. As a reflection of the town’s egalitarianism, Scott says, it wasn’t unusual to see millworkers and the chair of the CDF on committees together.

In the 1960s the Community Development Foundation bought up big tracts of land outside the town limits that would eventually serve as industrial parks. Now the city leases the properties to companies that relocate to Tupelo, then plows the proceeds back into the community.

Tupelo’s North Mississippi Medical Center is the largest non-metropolitan hospital in the country. What seemed to impress the Vanderbilt visitors most was the all-for-one spirit for which the Reeds themselves served as exemplars. The family, notes Victor, owns a century-old clothing business, the largest in town. But they actively solicited big-box competitors like Wal-Mart to enter the local market—a strategy that runs counter to what students traditionally learn in business school.

“I was surprised by how intrigued the students seemed to be with that,” says Scott Reed. “It didn’t seem like rocket science. There was an understanding that, if the community thrives, we’re going to thrive with it.”

If the strategy hindered the Reeds’ business, it doesn’t show. Along with two locations in Tupelo, the family also operates stores in Starkville and Columbus, Miss. “We’re a ring, not a chain,” laughs Jack Jr.

Partnering for the Future

The business lessons from Tupelo have not been lost on the newer generation of Vanderbilt students intent on changing not just their corner of the world but the whole global village. “Tupelo can be a story of inspiration,” says Sharran. “They have an amazing interaction between public and private enterprise. The CDF straddles that line. Private organizations just cannot do it all.

“They have a lot to teach us: Take a long-term view, and lay a foundation for our children and their children so the community can develop and grow. They had projects lined up 30 or 40 years out. Yet a vision is not enough. Selflessness is what guided that community.”

Says Scott Reed: “I think the students’ biggest takeaway is that there’s nothing we’re doing that others can’t do. If you figure out how to replicate this model, you can make strides for eliminating poverty.”

One day was more than enough to energize the group into thinking about opportunities Tupelo might offer. One possibility, suggests Srivatsaa, is a cross-disciplinary academic case study of Tupelo’s development. “Project Pyramid is perfect for that because no other organization encompasses so many disciplines across the university. Peabody students could study the educational system. Medical students could study the health care system. There’s a strong tie between every area of Tupelo and every area within our group.

“We have something spectacular in our own backyard with a strong Vanderbilt connection that needs to be nurtured.”

“I’m really excited about creating a more formal partnership with Vanderbilt so we can have the input of these really bright young people coming in here every year,” says Jack Reed Jr. “It certainly is a win/win.”

Igleheart Meanwhile, Tupelo is becoming more integral to the work of Project Pyramid. Vanderbilt Professor of Economics James Foster—who, says MBA student Ryan Igleheart, “knows more about Tupelo than anyone at Vanderbilt”—has discussed teaching a Project Pyramid-related course at Owen in the future. For the first time, there will be short courses about Project Pyramid at the Divinity and Law schools. Igleheart, who serves as President of Project Pyramid, will lead a second group from Vanderbilt to observe and learn in Tupelo. “Our next step,” he says, “is to adapt their model to other places.”

Those places may include Bangladesh, where, building on previous Project Pyramid efforts, Vanderbilt students will return in December and again next spring to work on a model village concept. They also could include Mozambique, where Project Pyramid participants may explore economic development strategies with Vanderbilt’s Institute for Global Health, which operates 10 AIDS clinics in the country.

The lessons of Tupelo also may reach to other business schools. Last fall Owen hosted a first-of-its-kind case competition on poverty alleviation. Teams from 35 schools, including Wharton, Chicago and Yale, participated. It’s part of an effort to plant seeds that could grow into Project Pyramid groups elsewhere. “The teams really started to embrace the excitement and energy of this project,” says Igleheart. Every week he receives e-mail messages from people around the world interested in getting involved. Which reminds him: Among growing numbers of tasks on Project Pyramid’s to-do list is a white paper on how to help others get started.

It’s the ripple effect, says Igleheart, that Project Pyramid has always intended to create. Ask students who have been part of it, and they’ll tell you those ripples have become strong currents in their own lives. Even after graduation Srivatsaa remains involved in building an advisory board of community leaders.

Igleheart, who is pursuing a Health Care MBA, says, “A big part of me wants to make this the focal point of my business career.” It’s a commonly heard sentiment—a reflection, perhaps, of a generational change and, perhaps also, of how Tupelo is a generation ahead of the curve. “There’s a point at which we’re all connected,” says Igleheart. “As a global community we have to succeed together. The world is waking up to that.”

-

Organic Chemistry

They are among the nation’s most compelling potential customers— the nearly 100,000 men, women and children who are in line for the fewer than 30,000 organ transplants that will be performed this year. That staggering gap is caused both by a scarcity of donors and by the fact that only 70 to 80 percent of the organs actually harvested can be utilized because of problems with quality or preservation.

They are among the nation’s most compelling potential customers— the nearly 100,000 men, women and children who are in line for the fewer than 30,000 organ transplants that will be performed this year. That staggering gap is caused both by a scarcity of donors and by the fact that only 70 to 80 percent of the organs actually harvested can be utilized because of problems with quality or preservation.The work of four members of the Vanderbilt Executive MBA Class of 2008 may help change the latter half of that equation. Their start-up proposal, developed for an Owen classroom and aimed at bringing to market a system that would better preserve donated organs, has earned the top prize in a prestigious business competition and has begun moving them toward the marketplace.

Classroom Origins

The company, Organ Transplant Technology (OTT), began attracting real-world interest while it was still a project in Bruce Lynskey’s entrepreneurial course, Creating and Launching the Venture, during Owen’s fall 2007 semester.

“In seven years of teaching at Owen,” says Professor Lynskey, himself a successful entrepreneur, “I can count on one hand the number of classroom projects I’ve seen with this much potential upside.”

Three panels of judges agreed with him. The OTT proposal wowed a group of venture capitalists brought in by Lynskey to rate student projects, reached the semifinals of the Wharton Business Plan Competition, then took top prize in the MBA Jungle Business Plan Competition in New York. For the team that developed and pitched the idea—Dr. Ravi Chari, Ted Klee, Drew Bordas and Fernando Sanchez—those milestones served as validation of both the quality of their teamwork and the importance of the concept itself.

We realized this was more than just a classroom project or a competition. This is something that can really save people’s lives.

~ Fernando Sanchez“We realized this was more than just a classroom project or a competition,” says Sanchez, who is Vice President of Finance and Treasurer of Gibson Guitar Corp.

“This is something that can really save people’s lives.”

The project is the culmination of two years of teamwork for Sanchez; Klee, who is Vice President of Square D/Schneider Electric Co.; Bordas, Director of Warehouse Management Systems for Ingram Book; and Chari, Professor of Surgery and Cancer Biology and Division Chief of Hepatobiliary Surgery and Liver Transplantation at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. The four were assigned to the team by Associate Dean of Executive Programs Tami Fassinger, who cites their disparate backgrounds as a source of strength.

“The goal of the study groups is to approximate all the skills you’d have in the executive suite,” she says, “and with this group you’ve got people representing four areas of functional experience as well as four different industries. Fernando Sanchez comes from the world of musical instruments and played the role of finance guy. You’ve got Ted Klee, who is the quintessential engineer and who understands manufacturing and operations. You have Drew Bordas, who understands distribution from a service industry point of view and has got the consumer piece. And then Ravi is the doctor at a leading medical center, bringing the scientific piece and contacts in the health industry.”

The quartet clicked at the week-in-residence at New Harmony, Ind., a getaway that kicks off the Vanderbilt Executive MBA experience, developing a style that was part think tank, part frat house.

From left, Dr. Ravi Chari, Ted Klee, Drew Bordas and Fernando Sanchez are the team behind Organ Transplant Technology. “They’re big practical jokers and very sarcastic,” says Fassinger, “but they genuinely enjoy each other’s company and have become very good friends. It was just that typical guy thing—making fun of each other, but out of respect. It was about all four of them getting the idea right.”

A Better Solution

They used first-year projects to hone their group approach, then weighed ideas for Lynskey’s class during the summer between academic years. The one they chose grew out of Dr. Chari’s work as head of Vanderbilt Medical Center’s liver transplant surgery team.

“Currently,” says Dr. Chari, “of the 40,000 to 50,000 potential donors, more than half are excluded because of concerns with organ preservation and quality. Of those that are harvested, 20 to 30 percent are not actually used, again because of concerns about preservation and quality. It is critical that organs are optimally recovered and stored.” That led him to the work of a European friend who was “having trouble commercializing a project that from a scientific standpoint had a lot of merit.”

The project took aim at improving the decidedly low-tech means now in use for transporting donated organs, which are placed in a solution in a zipped plastic bag and carried on ice in a portable cooler. That technique risks damage to the organ through freezing or temperature variation, and greatly limits the sustained viability of a donated organ. At present the limits are six hours for a heart, 12 for a lung or liver, and 24 to 30 for a kidney. Work done in part by Dr. Thomas Van Gulik of the University of Amsterdam brings two improvements to the process. The first is a system driven by compressed air that circulates the solution through the organ, constantly supplying it with oxygen and nutrients designed to prolong its useful life. The second is an improvement in the perfusion solution itself. Both can be used in an easily portable container that keeps the organ at a stable low temperature.

In addition, one of Dr. Chari’s colleagues at Vanderbilt, medical student Clayton Knox, had developed and patented with Dr. Chari a compound designed to improve the performance of the perfusion solution even further.

The others embraced Dr. Chari’s proposal enthusiastically.

“Ravi’s idea surfaced pretty quickly because it was real,” says Bordas. “It was no contest, really.”

Bordas, Klee and Sanchez all acknowledge the centrality of Dr. Chari’s role and the importance of his technical knowledge and contacts, but Dr. Chari himself is quick to return credit.

“From a logistics standpoint,” he says, “Drew is outstanding. Ted is all over the strategy and the operations side, and Fernando is great with the financial side, so each brought different areas and perspectives. A good thing about them is that they aren’t in the medical field, and they brought a real business perspective and asked demanding questions: ‘The science is good, but how can we monetize the idea so that it’s something people would actually buy?’ They pressed those issues further than a roomful of my colleagues would, and so we were able to turn a great idea into a marketable business plan people would be interested in.”

The strength of the team and its presentation was clear by late November, when Lynskey had his students present a working draft of the proposal, weeks before their final presentation.

They submitted their draft, and I brought it home and read it again and again, looking for something I could say was wrong with it. My only comment back to them was, “You need a nice presentation cover for this.” I’d never seen anything like it.

~ Professor Bruce Lynskey“Ravi’s team submitted its draft, and I brought it home and read it again and again, looking for something I could say was wrong with it,” says Lynskey, “and my only comment back to them was, ‘You need a nice presentation cover for this.’ I’d never seen anything like it.”

By the time of the in-class, end-of-semester presentation to a six-member panel of venture capitalists, the team’s message had been finely honed. Each panelist had $5 million dollars in imaginary money to distribute among 10 team proposals, and OTT garnered about two-thirds of the $30 million available.

“As they started talking about our proposal,” says Sanchez, “I turned to Ravi and said, ‘You’d better give them your business card. This thing has legs.’”

From Competition to Market

The team had already entered the Wharton Business Plan Competition, which requires that one member of the team be pursuing a Wharton MBA. That was exactly what Knox, who was still working toward his M.D. at Vanderbilt, was doing, following in the footsteps of his mentor, Dr. Chari.

“I realized,” Knox says, “that in academia, there are all these great minds and great ideas, but not a lot of people know how to get them out of the lab. Scientists are much better at thinking up new ideas than commercializing them.”

Professor Lynskey’s course had guided them toward doing just that.

“We never would have gotten this far had we not been in a program that forced us to think the project through and commit it to paper,” says Klee. “And I don’t think any of the guys in the group ever would think about doing something like this on his own, but put us together as a group, each with our own sets of talent and experience, with the university training us around these aspects important to developing a business plan, and it’s not that long of a putt.”

Their success continued as they were named semifinalists in the Wharton competition.

“When that announcement came out,” says Bordas, “The Wall Street Journal piece cited five ideas and ours was one of the five. Some of the judges said it was the best paper they’d seen in five years, and we said, ‘We should think about this more seriously.’”

They had entered the Jungle competition at the urging of Professor Lynskey. Their win capped an incredible run for what had begun as a classroom project and convinced them to pursue the company’s future, beginning with a return visit to Lynskey.

“The great thing about Bruce,” says Bordas, “is that he’s been there and done that. When you have a guy teaching you about starting companies who has started them and been very successful at it, that just gives the whole course a ton of credibility. And when we went back to him and said, ‘This looks real. What should we really do next?,’ he was able to have that dialogue with us. That’s one of the things you get by going to a university like Vanderbilt.”

The team has never lost sight of the underlying importance of the endeavor.

“More and more often, less-than-ideal organs are used, which is an unfortunate but necessary practice to manage the long waiting list,” they write in their business plan. “Ultimately, OTT’s goal is to improve the size and quality of the organ pool available for transplantation in order to increase the number of transplants performed each year and reduce the organ waitlist.”

“It’s pretty clear,” adds Dr. Chari, “that we’re excited about moving ahead with this work and with ironing out the agreements we need to get under way.” To that end, they are working to effect an agreement with the Amsterdam-based developer of the solution and the air-drive system, while awaiting approval of both in the United States and the chance to deliver the concept to a waiting marketplace.

“Some of the significant liver transport units around the country are eager to get it and put it into trials,” says Klee.

A Rewarding Experience

The value of the team’s Owen experience has become more apparent, with Dr. Chari seeing his MBA as a key to better positioning in a changing medical climate.

“Looking at the landscape of health care right now,” he says, “a premium is being placed on improved processes and improved function in the medical field. Traditional medical education gears you toward science and clinical applications for patients, but cost efficiency, process efficiency and other business principles constitute an important language to be able to speak.”

His Owen experience, he says, “changed not only how I think but how I analyze a situation—not just what information to use, but what questions to ask and where to look for that information.”

For Knox, who is part of OTT’s management team, the project’s success is “extremely rewarding and extremely validating in terms of the need for people who can understand both worlds, who can understand medicine and the business side of it—something Vanderbilt is especially good at fostering.”

As noble as the medical aims of OTT are, its principals are equally thrilled with the personal rewards of their Owen experience.

“We had a great class,” says Bordas. “Meeting those 40 or 50 people, I think, is going to pay dividends down the road. And within our group, I’m very grateful to have that core set of people you can bounce things off of. I consider them very good friends as well as mentors.”

Those friendships are likewise a prime reward for Sanchez.

“First and foremost,” he says, “I now have three or four people who I consider great friends for life. They are just good people from varying backgrounds, and I wouldn’t have met them any other way.

“The experience,” he says, “is a great one from a personal standpoint.”

-

Owen Mergers

If we’re to believe Sigmund Freud, then all that matters is love and work. Certainly everyone endeavors to succeed in both, but far too often one gets in the way of the other. That is, unless you’re like the couples profiled below. Although decades apart, they all have something in common: They have struck a happy balance between their married lives and their careers, and they owe much of that happiness to the place that put them on the path to both—the Owen School.

If we’re to believe Sigmund Freud, then all that matters is love and work. Certainly everyone endeavors to succeed in both, but far too often one gets in the way of the other. That is, unless you’re like the couples profiled below. Although decades apart, they all have something in common: They have struck a happy balance between their married lives and their careers, and they owe much of that happiness to the place that put them on the path to both—the Owen School.Minh-Triet Lethi Tucker, MMgt’72,

and Greg Tucker, BA’68, MMgt’71Little did Greg Tucker know that an admissions brochure he designed would attract an honors student from Vietnam who would later become his wife. Greg was a member of the founding Vanderbilt GSM class, which met in the University Club basement. He remembers the day Minh-Triet’s application arrived at the admissions office, where he worked. “I opened the letter and thought, ‘I have to meet this young lady.’”

Greg was in Dean Igor Ansoff’s office, which overlooked West End Avenue, the day Minh-Triet arrived on campus. “I looked out the window, and coming down the sidewalk was this beautiful creature,” he says. Their initial introduction, however, didn’t go as well as he’d planned. Minh-Triet explains that she had a difficult time understanding Greg’s Southern accent.

After graduation Minh-Triet joined the MITRE Corp. in Washington, D.C., as a consultant. Greg continued at the school as its first Director of Admissions and Placement. In 1976 Greg enrolled in law school in Washington, and in 1977 they married in Constitution Gardens. During the Reagan administration, Minh-Triet was on the White House staff as Senior Policy Analyst for Science and Technology, while Greg practiced law with the Covington & Burling firm.

The couple dreamed of retiring to a farm, and it just so happened that one neighboring Greg’s aunt’s property outside Nashville became available at the same time his client HCA asked him to return to Middle Tennessee. It seemed “divinely planned,” says Minh-Triet. Today they are proud parents of a daughter and son, Brigitte and Burney, who are 2006 and 2008 Vanderbilt graduates, respectively.

Maria Renz, MBA’96,

and Tom Barr, MBA’98As a Project Manager at Hallmark, Maria Renz was puzzled by a seemingly overconfident Owen summer intern. “I was a bit taken aback … the other two interns contact-ed me when they came to town. They’d say, ‘Oh yeah, Tom Barr is here,’ and I’d think, ‘Who the heck is Tom Barr?’”

Renz tracked Barr down, and they soon became friends. After graduation Tom joined GlaxoSmithKline in Pittsburgh. Renz was then with Kraft Foods in New York City, where GlaxoSmithKline’s ad agency is located. They began dating, even after Renz moved to Seattle to work for Amazon. Tom began taking Friday night flights from Pittsburgh to Seattle and then red-eyes home on Sunday.

“After a year we thought, ‘This is crazy. We have to figure out how to make this work,’” Renz says.

Before they even began exploring opportunities, a headhunter contacted Tom about coming to work for Starbucks Coffee Co. Tom is now the Vice President of North American Marketing for the coffee retailer, while Renz is a Vice President with Endless.com, Amazon’s shoe and handbag Web site.

“Whenever I need business advice or want to talk to my best friend, I turn to Tom. We have a great network of friends through Owen,” she says.

Tom serves on the Owen Alumni Board, and the couple participated in last winter’s Marketing Camp. They also have two children—prospective students for the Owen classes of 2031 and 2032, no doubt.

Donna Zavada Wilkinson, MBA’93,

and Jeff Wilkinson, MBA’92Donna Wilkinson knew it was true love when Jeff agreed to help her cater an engagement party for Owen’s Director of Corporate Relations, Peter Veruki. The commitment meant that Jeff, a diehard Duke fan, would miss the NCAA regional finals basketball game between the Blue Devils and Kentucky—a game that many pundits consider the best ever played among the college ranks. Donna, at the time, worked with Veruki in the Owen placement office.

“I used to go into the placement office every day ostensibly to find a job,” laughs Jeff.

The two first met during an ethics breakout session Jeff helped facilitate during first-year orientation. He remarked about the prevalence of Duke graduates in the group, and Donna, a Duke alum herself, introduced herself afterwards. Jeff moved to Atlanta to work for Accenture after graduation, while Donna began her career with Sara Lee in Memphis, Tenn.

The couple timed their December 1995 wedding to coincide with the completion of her management training at Sara Lee and a transfer for both of them to Dallas.

The Wilkinsons both serve on the Owen Alumni Advisory Board and live in Indianapolis with their two young daughters. Donna is the Vice President of Human Resources with Pacers Sports & Entertainment, while Jeff is a Partner with Accenture. Says Donna, “We have a special place in our hearts for Owen. I loved my time there, and it was a bonus that I met my husband there.”

Vicki Simons Heyman, BA’79, MBA’80,

and Bruce Heyman, BA’79, MBA’80When Vicki and Bruce Heyman paired up during a New Venture Creation course, they had no idea how it would change their lives. Taught by longtime Owen Professor Ed Bartee, the course not only introduced them to some of their closest friends but also sparked a romance that would last a lifetime.

“Our first date was Lamar Alexander’s governor’s ball,” says Bruce, a Managing Director for Goldman Sachs, who is the firm’s recruiting captain for Vanderbilt. The Heymans have remained very involved with the university, serving as co-chairs of their 25-year reunion in 2005. Vicki also has served on the Vanderbilt Alumni Board and on the Hillel Board for the Schulman Center for Jewish Life.

“Our participation has been exciting for us because we’ve been part of the upward trajectory of Owen. It’s also come at a very exciting time because our kids have been going through the college process,” she says.

Their youngest daughter, Caroline, is a high school senior, and middle daughter, Liza, is a Vanderbilt junior. Their oldest child, David, is 23 and an analyst in the foreign currency sales and derivatives department at JPMorgan, which, coincidentally, is the position Vicki held for four years after working in recruiting at Bankers Trust.

Elaine Wu, MBA’04,

and Jon Weindruch, BA’98, MBA’04Elaine Wu and Jon Weindruch’s first date, an informal meet-up at a coffee shop, never happened. “Elaine stood me up,” jokes Jon. In reality, Elaine was a newly trans-planted international student stuck outside of downtown Nashville during a thunderstorm without a car or Jon’s cell phone number.

The two first met during a retreat about ethics sponsored by Cal Turner, which brought together students from Owen, as well as the Divinity School, Vanderbilt Law School, and the School of Medicine. They started dating during their second year, and Jon, who founded the Web-site strategy consulting company Websults while at Owen, followed Elaine to North Carolina, where she worked for Hanes after graduation.

In May 2005, during a return visit to Nashville, Jon proposed to Elaine at Percy Warner Park. They were married six months later in Taipei, Taiwan, by a pastor who had pursued his Ph.D. at Vanderbilt Divinity School. Some of their Owen friends also traveled to the wedding.

Elaine is currently Director of Internet Marketing for Victoria’s Secret, which operates the biggest retail apparel-accessory Web site in the United States. The couple lives in Columbus, Ohio, and Jon travels regularly to Nashville to consult with several clients, including the Owen School, which he has been assisting with Internet marketing.

-

Headlines from Around the World

Throwing Caution to the Wind

Throwing Caution to the WindYesterday’s stock market tumble is the direct result of the deregulation of the financial system during the ’70s, experts say. “It was another example of an asset bubble that appears periodically. An economy will disregard risk, and when people see another investor making money by investing in an asset, others will throw caution to the wind,” explains Nicolas Bollen, a finance professor at Vanderbilt University’s Owen School.

McClatchy News Service, Sept. 16

Trade Off

International trade remains an evergreen fissure running through U.S. politics. While John McCain has been firm in his defense of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the Democrats have promised, albeit without specifics, to renegotiate treaties to protect U.S. workers. Luke Froeb, a free enterprise expert at Vanderbilt University, identifies this as a key ideological gap. He argues: “Renegotiating NAFTA would make our economy a lot less flexible. It would reduce income and make us all worse off.”

The Guardian (U.K.), Aug. 31

Clinical Trial and Error

Many institutional review boards do an exemplary job, keeping scientists on the ethical up-and-up, but “hyperprotectionism,” according to the Journal of the American Medical Association, “can have a stifling effect on research productivity.” One measure of that might be the number of new compounds approved by the Food and Drug Administration. It averaged an abysmal 19 last year—the fewest since the early 1980s. Or you can measure it by how long it takes a clinical trial for cancer to get off the ground: 171 days of red tape, finds David Dilts of the Owen School.

Newsweek, Aug. 11

Striking Gold

Olympic advertisers will spend more than $1 billion for U.S. airtime alone, although some say they will not get their money’s worth. In a time when it’s harder to win by simply offering a better product, the goal of a lot of advertising is to arouse positive feelings that forge lasting bonds with consumers, says Jennifer Escalas, a Vanderbilt professor. This year’s Olympic ads fit squarely with that goal. McDonald’s, for example, isn’t trying to sell a specific burger but to “build a relationship,” Escalas says. “If you feel good about the Olympics, that good feeling should spill over to the brand.”

MSN.com, Aug. 7

Full Disclosure?

Researchers have found that the Security Exchange Commission’s Regulation Fair Disclosure rule (Reg FD) has curtailed the amount of information that companies disclose to the public. Baljit Sidhu from the Australian School of Business, Tom Smith from Australian National University, and Robert Whaley and Richard Willis from the Owen School studied the effect of Reg FD by comparing cost components of the bid-ask spreads of Nasdaq-listed stocks in the months before and after Reg FD went into effect. “While Reg FD gave everyone the same info at the same time, what it’s done is it has made firms release less information, and it’s driven up the cost of trading,” says Whaley.

CFO.com, Aug. 1

On the Margins

The collapse of SemGroup LP, which filed for bankruptcy after losing $2.4 billion on energy contracts, has focused attention on margin requirements. Financial-market experts point out that while trading firms may struggle with margin requirements, increased margin doesn’t become an issue unless the trade is a loser to start with. “It’s a standard argument” when traders “get into trouble,” says Hans Stoll, a finance professor at Vanderbilt.

The Wall Street Journal, July 29

-

In a Tailspin?

Michael Lapré, an Owen faculty member who studies operations and performance in the airline industry, sees many challenges ahead for the major airlines. Maintaining customer satisfaction will continue to be a problem, he predicts, as fuel costs continue to soar and the industry works to keep costs down.

Michael Lapré, an Owen faculty member who studies operations and performance in the airline industry, sees many challenges ahead for the major airlines. Maintaining customer satisfaction will continue to be a problem, he predicts, as fuel costs continue to soar and the industry works to keep costs down.“Right now the biggest issue is cost,” says Lapré, the E. Bronson Ingram Associate Professor in Operations Management. “They need to figure out an appropriate cost structure that makes it at least appealing to compete with an airline like Southwest. That’s not easy. You want to pay your employees appropriately. But that’s tough because other airlines, the discount airlines, have much cheaper labor. Then there are fuel costs, and figuring out how many different types of planes you can profitably have in the fleet. So there are cost-structure issues, fleet issues, labor issues. It’s not easy.”

Indeed, the airline industry today is facing a triple threat from rising costs, customer dissatisfaction, and an aging air-traffic control system, spurring some industry analysts to compare the current environment to the post-9/11 era of bankruptcy filings and extreme belt-tightening.

While US Airways CEO Doug Parker and others see mergers and acquisitions as an inevitable mechanism for airlines to consolidate costs, it is well known that mergers create problems, at least for the short term, and can create customer dissatisfaction.

“There are going to be more mergers,” Lapré says. “I do know that mergers and acquisitions can be troublesome. For example, the two airlines’ information systems can have trouble communicating. It takes a long time to integrate the information systems. It’s actually much easier to start from scratch than patch different types of systems together.”

Within the next few years, the number of major carriers in the United States will be reduced from the current six—US Airways, Delta, American, Northwest, United and Continental—to four and perhaps fewer, he predicts.

Within the next few years, the number of major carriers in the United States will be reduced from the current six—US Airways, Delta, American, Northwest, United and Continental—to four and perhaps fewer, he predicts.

Lapré, the author of an award-winning paper on performance improvement paths in the U.S. airline industry, focuses his current research on longitudinal data from the industry—data he says is easier to procure than in some other areas of business because the airline industry is so tightly regulated.

“I am focusing on the lessons learned about what worked well,” he explains. “I have found that you really must start with quality first. If you start cutting costs and don’t pay attention to quality, it’s going to be detrimental in the long run.”

Lapré says it’s hard to predict when flying may become more pleasurable and profitable again.

“Security issues are going to make flying a bit of a hassle. And now airlines are playing with charging for baggage. The so-called legacy airlines—those formed before the current era of discount carriers—began their operations in an era when oil was much cheaper and costs were less of an issue. Discount carriers, on the other hand, started from a cost-control position, so they can afford not to trim such services.

“Discount carriers are at an advantage because they turn the plane around so quickly on the ground,” he says.

But even discount carriers experience delays due to the antiquated air-traffic control system. “I think the industry is waiting for some technological advances that will make it easier for more planes to be in the air. Right now it’s almost full in the air. It’s too congested.”

Lapré repeatedly returns to the linchpin that will make or break an airline: quality.

“No airline can forget about quality. And that just means doing the basic things right and making sure customers are happy. Satisfied customers can become loyal customers, who will keep coming back.”

-

Riding Out the Turbulence

Grounded. In airplane parlance, it’s an ironic way to describe someone who oversees the fifth largest airline in the country, but that’s exactly how friends and colleagues of US Airways Chairman and CEO Doug Parker, MBA’86, view him. While he’s adept at managing the 30,000-foot view, they say he remains one of the most down-to-earth people they know—even as his embattled industry confronts soaring costs and plummeting customer satisfaction.

Parker, who steered America West Airlines from bankruptcy to profitability in the ’90s and then engineered a successful merger with US Airways in 2005, launched his career in the airline industry with American Airlines. The Dallas-based company offered him his first post-MBA job during a recruiting visit to the Owen School.

“The fact of the matter is, I don’t think I would have been in this business if it weren’t for Vanderbilt,” he says from his company headquarters in Phoenix. “American Airlines recruited only MBAs, and they did so only at a very select group of schools. Because of the Vanderbilt connection, I was able to get hired.”

In recent years Parker’s strong views about the value of mergers and consolidations in restoring the industry to profitability have earned headlines. A bid for Delta Air Lines, initiated in late 2006, was rebuffed (a Delta-Northwest merger was announced earlier this year), and talks with United Airlines stalled. But Parker remains characteristically optimistic, despite cost-cutting imperatives driven by rising oil prices.

Team Building

Parker saw the merger of America West and US Airways as a mechanism for building on the best of both worlds. The two airlines had similar cost structures and together created a larger customer base and more business markets. “We didn’t raise prices; it was about making us both more efficient,” Parker explains.

The merger, though profitable, wasn’t without snags, including the headaches of integrating two information systems. There have also been new challenges, such as skyrocketing oil prices and growing problems with customer satisfaction, which US Airways has tackled with spectacular success, going from last place to first in on-time arrivals during the first six months of 2008.

Even after 20 years in the business, Parker maintains a relish for grappling with complex problems that his classmates remember from his days at Owen. “We’ll figure out a way to make this industry profitable again, even if the oil prices remain high, but it will be a different industry,” he says.

No doubt he will lead the company toward making necessary innovations a reality with a focus on team building, his signature management style.

Parker’s team-centered leadership style harkens back to his days playing high school and college football, says Elise Eberwein, Senior Vice President for People and Communications at US Airways, who has worked with Parker for five years.

US Airways operates approximately 3,200 flights per day and serves more than 200 communities around the globe. “He is completely ‘relatable’ to employees of all levels and backgrounds. By relatable, I mean he laughs at the same jokes, is so incredibly down-to-earth, and cares about things that matter to our people as opposed to just the 30,000-foot view. Don’t get me wrong—he cares about that, too—but he is very connected to the emotional things that matter to people day in and day out at their jobs,” says Eberwein, who estimates Parker spends 50 percent of his time getting to know employees at all levels.

She says he truly wants divergent views at the table and has created a culture where differences in opinion are handled respectfully. “I’ve worked for several CEOs and been around a lot of high-level executives. Doug is by far the best team builder and ‘head coach’ I’ve seen,” she says.

Parker made news after the US Airways-America West merger when he refused a bonus based on America West’s performance the previous year because he felt it was unfair to US Airways employees whose salaries had been cut. More recently, he made a large personal investment in company stock.

A Reflection of His Character

A Reflection of His CharacterIt did not surprise any of Parker’s Owen friends to see him step up and make a large investment during a dark time for the industry, according to David Hornsby, MBA’86, Owner of Executive Travel and Parking in Nashville.

“Doug has always had this ‘never say die’ optimistic bent. … That’s just the way he’s always been,” says Hornsby, who has remained close to Parker since their days at Owen. Hornsby and others describe Parker as a fun-loving guy and a generous friend who is always punctual, neat and full of ideas.

“Doug has always been extremely analytical. He was always coming up with a ‘system’ for everything. We put a lot of faith in Doug’s systems, and I’m sure he is a master of systems at US Airways,” Hornsby says.

Owen School Dean Jim Bradford says Parker’s focus on finding systems that work rather than copying existing operations was a huge factor in the success of the US Airways-America West merger. “It’s a reflection of his character, organization and strategic initiative that when he rebuilt America West, he didn’t just copy a successful airline like Southwest; he made strategic changes that saved costs but with an ultimate focus on customer service,” Bradford says.

Parker and Hornsby are part of a tight-knit group from the MBA Class of 1986, and Parker says the strong friendships he made at Owen were the most important part of his graduate school experience.

Bradford recalls how well Parker’s friends from Owen have helped keep him grounded, particularly right before the airline executive was slated to speak at a class reunion gathering: “Here’s a successful guy speaking at a ‘no-risk’ conference. One of the things his classmates did the night before he was speaking to the entire group was pepper him with really nasty questions they were pretending to prepare for the next day. Of course, they love him to death. It was funny to watch him get a little nervous.”

Parker met his wife, Gwen, a former flight attendant, through mutual friends while living in Dallas. It was a courtship witnessed by Owen classmate Jim Loftin Jr., MBA’86, who also worked for American Airlines after graduation.

“I knew when Doug had found his bride,” says Loftin, now President of JDL Management and Consulting in Dothan, Ala. “I was visiting him in Dallas and, for the first time I had ever seen, he was particularly interested in attending a specific party. Doug was always a go-with-the-flow kind of guy. When we arrived, I noted Doug had a bit of uneasiness I had never witnessed before. On more than one occasion that evening, Doug would say, ‘Hey Jimbo, come on, let’s go over here.’ It was always within 10 feet of Gwen. She paid him no attention that evening, but it was only a matter of time before those two would tie the knot.”

The Parkers are the parents of three children—Jackson, 13; Luke, 10; and Eliza, 8—and live in Paradise Valley, Ariz.

“Doug’s a great dad and husband,” says Andy McCain, MBA’86. “He’s managed to balance that pretty well with being CEO in an industry that’s had more difficulty than any other that size.” McCain, who is Vice President and Chief Financial Officer of Hensley & Co., is another member of that tight-knit group from the Class of 1986. He lives in Phoenix and is one of Parker’s closest friends.

One Crisis After Another

One Crisis After AnotherParker spent five years at American in Dallas, holding a variety of financial management positions, before joining Northwest Airlines in 1991. His titles at Northwest included Vice President and Assistant Treasurer, as well as Vice President of Financial Planning and Analysis.

“Northwest was going through an LBO (leveraged buyout) and looking to hire new management to improve their team,” Parker recalls. “I loved my time at American, but I was ready to do something where I could make even more of a difference by building some things really from scratch.”

After four years with Northwest, he was recruited in 1995 at age 33 to become Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer at America West, based in Tempe, Ariz. “It was a smaller airline going through similar things Northwest had gone through a few years before. The new management was trying to build a new team. It was a great opportunity for me that I couldn’t pass up. I’ve been here ever since,” Parker says.

He was named CEO of America West on Sept. 1, 2001. “It was a good 10 days,” he says wryly.

The industry, already troubled before the Sept. 11 disaster, lurched into crisis mode after those events. Parker led his company through a loan guarantee process that helped turn it around by 2005, the same year America West initiated a merger with US Airways, then in bankruptcy and in danger of shuttering its operations. By 2007 the combined airline, with Parker in the leadership role, earned $427 million in profits.

Unfortunately those profits are now being eaten away by huge increases in oil prices. The company is predicting that spending on fuel alone could increase by $1.8 billion dollars in 2008 over the previous year. Fuel prices now represent a staggering 40 percent of the operating budget, Parker says.

Although the current obstacles are daunting, Parker recalls that in 2001, many pundits similarly believed America West “was done.”

“Survival’s a great motivator,” he says. After Sept. 11 the airline was forced to better understand customers’ needs, making changes accordingly, and to redefine the airline with a low-cost structure.

But America West executives knew the operational turn-around might be tenuous. “So as we looked at America West, we were very concerned about our viability because we had an airline that never had the same revenue generating capacity” as other airlines, he says. “We made up for it with lower cost structure, but we had cause for concern.”

The merger with US Airways was an opportunity to expand into more business markets and afforded a larger customer base.

“I recall vividly when we were putting this merger together that there was concern about oil prices, which were then $50 a barrel,” he says. Company managers were confident that they could succeed despite the high costs of fuel. “But when oil prices jump from $90 to $145 in a matter of months, that has a profound impact on our business. There’s a lot of financial turmoil in the business that we’re not immune to.”

Tackling Problems Head-On

Parker, always one to see the silver lining, says soaring oil prices have similarly forced the industry to address airport capacity issues. “Six months ago we were spending a lot of time working on how to fix the congestion issue,” he says. “It was much of what everyone was talking about. The fact of the matter is, oil fixed that. We were forced to take 10 percent of capacity out right away. It will come back one day, but the impact of oil overwhelms everything else.”

Six months ago we were spending a lot of time working on how to fix the congestion issue. The fact of the matter is, oil fixed that. We were forced to take 10 percent of capacity out right away. It will come back one day, but the impact of oil overwhelms everything else.

~ Doug Parker